WTF is going on with the climate?

You have questions, I have questions too.

I have been getting a lot of questions from reporters that basically boil down to, “What the $@#%*^ is going on with the climate system?”

This plot shows what people are concerned about:

As you can see, the global average temperature has increased by 0.5°C over the past year. That’s a lot, and it will make 2023 the hottest year in the observational record (going back to the mid-19th century), and possibly the hottest year in the past 125,000 years.

What could be driving this rapid warming? One way to approach this question is to examine all of the mechanisms that could plausibly be responsible and assess whether there is evidence supporting any particular mechanism — a climate whodunit, if you will.

Here are the usual suspects:

Global warming

Aerosol decreases

El Nino

Hunga Tunga volcano

Let’s take these one at a time, starting with the last one on the list. Could it be the Hunga Tunga eruption? No. Just no.

The next suspect is global warming. This is very unlikely to be the cause. The rate of global warming is around 2°C per century; 0.2°C per decade; 0.02°C per year. Even if you take into account acceleration from 0.02°C per year to 0.03°C per year, warming of 0.5°C over the past year is too fast by more than a factor of 10. So that’s not it.

What about aerosols? This should technically be included in global warming, but a lot of people are talking specifically about aerosols now, so it’s worth discussing it in detail.

Aerosols are solid or liquid particles that are so small that they have negligible fall speed, so they stay in the atmosphere for weeks. Humans emit aerosols and aerosol precursors and, once in the atmosphere, these aerosols cool the climate by reflecting sunlight back to space. These aerosols are also one of the primary components of air pollution, killing millions of people every year. As countries around the world have cleaned up their air, aerosol abundances have declined, reducing aerosol cooling, thereby warming of the climate.

This is certainly happening, but it’s also slow. Zeke wrote an oped in the New York Times about two months ago where he included this plot:

It shows that aerosol reductions have caused maybe 0.1°C of warming over the last decade. That’s a lot and we need to carefully track that, but it’s not enough to explain the rapid warming of 2023.

Finally, there’s El Nino, which is a form of unforced climate variability. It is part of a repeating 3-5 year cycle that arises due to non-linear interactions between the atmosphere and ocean. The plot below shows satellite measurements of global average temperature, color coded by whether the Earth is in El Nino (the warmer phase of the cycle) or La Nina (the cooler phase):

This plot shows that, during El Nino, the planet warms; during La Nina, the planet cools. So it’s reasonable to wonder whether this is what’s driving the incredible warming of 2023.

Previous research (e.g., Foster and Rahmstorf, 2011) and my own calculation shows that the global average temperature changes by about 0.1°C per unit change in the El Nino/Southern Oscillation index.

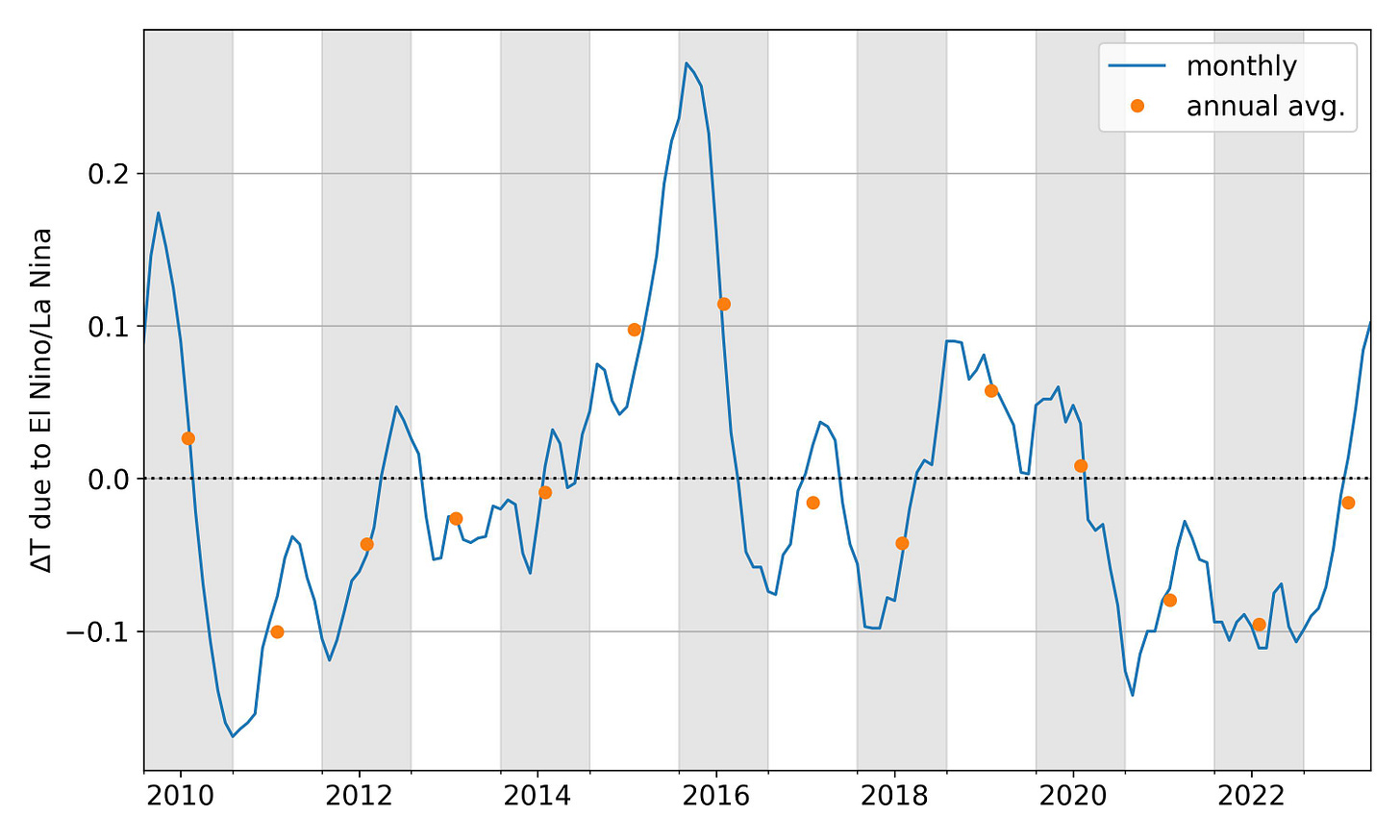

Once we know that, we can then use it to estimate what impact El Nino cycles had on the global average climate:

This plot shows a few interesting things. First, you can see how big the El Nino of 2016 was. You can also see that 2023 started in a reasonably strong La Nina and then transitioned to an El Nino (the blue line shows the monthly data). This increased global average temperature by about 0.2°C — about 40% of the warming seen in 2023.

Because 2023 started in a reasonably strong La Nina, which then transitioned to an El Nino, the net effect of La Nina/El Nino cycles on 2023 (so far, at least) is pretty close to zero (the orange dot shows the annual average). So if 2023 ends up being a record-breaking year, it won’t be due to the El Nino.

Overall, the warming of 2023 seems too large to be explained entirely by any of the suspects. It’s somewhat reminiscent of “the pause” from the 2000s and early 2010s when global warming slowed down and scientists struggled to explain it. That turned out to be due to natural variability persisting over an extended period.

The current situation will probably end up being similar. Our estimate of the impact of El Nino comes from linear regression, but our present situation may be unique: we just flipped from an unusually persistent triple-dip La Nina (2020-2022) into a strong El Nino. This may mean that El Nino is having a bigger impact this year than it would on average.

What does 2023 mean for the future? Probably not a lot. If you want to know what the future of the climate is, your best bet is to look at the climate model predictions. Climate models have done a great job predicting global average surface temperature, so the predictions deserve a significant amount of deference. They are predicting an acceleration of the warming as greenhouse gas emissions continue and aerosols decline, but not a continuation of the extreme warming of 2023.

Gwynne Dyer, a Canadian journalist living in London, has just written in an article "Viva the almost perfectly useless COP":

"How did everybody fail to factor the probability of a big El Nino into their estimates of the speed of warming? Well, lots of people knew it was due around now, but nobody had the job of watching for it and adjusting the climate predictions accordingly.

How did nobody foresee that the cleanup of pollution in Chinese cities and the International Maritime Organisation’s 2020 decision to cut the sulphur dioxide content in the fuel emissions of 60,000 merchant ships from 3.5% to only 0.5% would lead to cloudless skies and a big jump in sunlight reaching the surface?

It’s the practical equivalent to a 0.5°C jump in average global temperature in just three years, but nobody saw it coming because nobody was tasked to look for that kind of unintended side effect."

I was a but surprised as Dwyer is usually reliable; I intend writing to the Otago Daily Times where I read it, but the article will appear worldwide.

You make a couple statements that seem somewhat contradictory.

"So if 2023 ends up being a record-breaking year, it won’t be due to the El Nino."

and

"This may mean that El Nino is having a bigger impact this year than it would on average."

For me it comes to down to looking for a suspect that can cause this kind of rapid increase and the only one that seems capable of such a change is ENSO.

When I look at the plot of average temperatures in Zeke's post from 23.10.23 at carbonbrief.org, https://www.carbonbrief.org/state-of-the-climate-global-temperatures-throughout-mid-2023-shatter-records/ , 2023 looks to me a lot like the ENSO transition years of 1997 and 2015, only bigger.

I will point you to another interesting analysis that was referenced at andthentheresphysics.com by Dan Neuman, https://dmn613.wordpress.com/2023/11/20/more-details-on-sep-oct/ . It is pretty impressive for a retired engineer, https://mstdn.ca/@dan613/109529967802520094 .

I guess I think the jury is still out on ENSO.