Why you can be confident that climate change made the Texas floods worse

the importance of testing the right hypothesis

Like clockwork, every extreme weather event triggers the same predictable response: climate misinformers shift into overdrive with cherry-picked data and misleading arguments, all in service to the argument that climate change didn’t make this event worse.

The devastating July 4th Hill Country floods were no exception. But, as described below, their arguments miss the target.

the playbook

The main argument making the rounds goes something like this: The IPCC says there's no trend in floods, therefore we cannot claim that climate change enhanced the flood.

The citation to data and the IPCC gives it a sheen of scientific authority. But there’s just one problem: this is the wrong question.

an analogy

Imagine there’s a fatal accident caused by a driver running a red light. Someone says the driver was texting, causing the crash. But another person counters, “Traffic fatalities aren’t rising, even though texting is increasing, so texting couldn’t have caused this accident.”

This is literally the argument that climate misinformers are making and I hope you can intuitively tell how dumb it is.

In reality, accident investigators don’t care about the trends. They’re going to focus on the details of this crash. If, for example, the driver’s phone records show they were texting at the moment of impact, they could confidently conclude texting contributed to this accident. This is true even if there were no long-term trends for such accidents.

Thus, we need to examine the details of this specific rain event. In doing so, the key question is whether climate change made this particular rainfall event more intense.

The logic here is straightforward. We start with the knowledge that the flood has already occurred. If climate change contributed to heavier rainfall during this storm, then that additional rainwater must go somewhere. And the only place it can go is where all of the other water is going — into the flooded region — thus increasing the severity of the flood. QED.

This direct physical argument holds true regardless of long-term trends in floods.

climate change increased the rainfall

So the important question is did climate change increase the intensity of the rainfall?

Before the rain event, the atmosphere over central Texas had near-record levels of atmospheric precipitable water over the Hill Country1, with — up to 2.5 inches, in the 99th percentile — creating ideal conditions for heavy rainfall.

With weak steering winds, thunderstorms moved very slowly and repeatedly poured rain over the same locations. From July 3 to July 5, the Hill Country received between 10 and 20 inches of rain. With little opportunity for runoff, rivers such as the Guadalupe rose rapidly — in some areas by more than 30 feet in just an hour or two — resulting in a catastrophic flash flood.

Basic physics tells us that warmer air holds more moisture. This fundamental fact creates the direct link between rising global temperatures and the extremely high atmospheric water content: humans are warming the climate, thereby increasing water vapor in the atmosphere, and more atmospheric moisture then produced more intense rainfall when the storms developed2.

double checking

One of the advantages of working in an atmospheric sciences department is that I can walk around the building and ask my colleagues what they think. One of my junior colleagues said he thought my logic was sound (“I think it is good! Nothing that is glaring on my end.”).

One of my curmudgeonly senior colleagues objected to making any statement about climate change increasing the rainfall; all you could say, he said, was that it increased the probability of the event.

Another equally curmudgeonly senior colleague3 said that, because the 1-day rainfall from a 1-in-100 year event in this region had increased around 10-15% in this region over the last 40 years, his best guess was that climate change increased the rainfall by about that amount, give or take.

Thus, as with any cutting edge scientific question, one finds a range of perspectives. Based on these conversations, as well as others I’ve seen on social media, I would estimate it’s likely to very likely4 that climate change made the rainfall more intense and, by extension, that climate change made the tragic flooding worse than it would have been in a world without climate change.

it’s hurricanes all over again

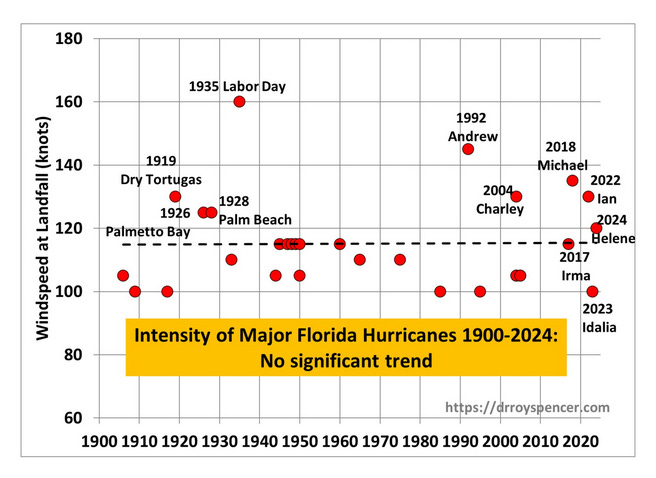

The exact same argument is trotted out whenever hurricanes hit a populated area. Climate misinformers are out in force saying, there’s no trend in hurricane (numbers, intensity). Or, if there is a trend, we can’t prove the trend is due to climate change. A closer look shows it’s not just the same arguments — it’s literally the same people.

But, once again, when you’re asking about the impact of a single hurricane, trends are not the most relevant information. Instead, you need to look at the individual event.

Take Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Attribution studies analyzing that specific event found that human-induced climate change made its record-breaking rainfall roughly 25% more intense.

And, as with the July 4 floods, adding that much more rain to a flood event undeniably made Harvey’s flood worse — even if there are no trends in the properties of hurricanes. In fact, just from simple physical arguments, we can be quite confident that any hurricane that hits land today is more destructive because of climate change.

what about the lack of flood trends?

It is notable that while precipitation is intensifying, there are no compelling trends in flood statistics. There are several possible explanations. First, measuring trends in extreme events is inherently difficult. By definition, extreme events are rare, so even a 50- or 100-year dataset may be insufficient to reveal a clear trend. For instance, a single 10,000-year event occurring in the 1930s could create an outlier big enought to completely wipe out an underlying trend driven by climate change.

Second, human interventions, such as the construction of flood control infrastructure, may be offsetting the effects of more intense rainfall. Finally, the historical data itself may have large uncertainties, an important issue in estimating long-term hurricane trends.

As curmudgeon #1 reminded me, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” The absence of a trend in flooding does not mean there is not a trend in flooding that’s buried beneath the noise and datan uncertainty.

In the end, the lack of flood trends does not invalidate the conclusion that climate change exacerbated specific events like the July 4 Texas flood, which is supported by direct analysis of the storm combined with simple physical reasoning.

Understanding these arguments isn’t just academic — it’s essential for how we prepare for the future. If we dismiss the climate connection to individual events because long-term trends are complex and hard to interpret, we’ll continue to be caught off guard by “unprecedented” disasters that are becoming all too precedented.

related

a previous TCB post on the Texas flooding

This may have been due to an influx of deep tropical moisture from the remnants of Tropical Storm Barry, although trajectory analysis shows a range of causes for the extreme humidity.

Climate change may have also reduced the storm’s movement, causing it to linger over the region and dump more rain. This connection is considerably more speculative, though.

it turns out that “curmudgeonly senior colleague” is redundant.

I’m using here the IPCC’s calibrated language, indicating 66-90% confidence. I’m being conservative here; I am quite confident that attribution studies will show a strong impact of climate change on this event.

A comment on TCs.

The energy imbalance at top of atmosphere is caused by increasing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases caused by human activities. Certain!

As a result the oceans are warming year after year and the air above the oceans are warmer and moister (relative humidity remains about the same).

The results is increased atmospheric activity. This is where the complexity arises, because wrt hurricanes and Tropical Cyclones (TCs) it might be manifested as:

increased numbers

increased intensity

increased lifetime

increased size

increased rainfall.

The increase in intensity is directly related to increased moisture. The numbers are instead expected to drop overall because of changes in atmospheric structure (increased stability). This is complex because although true for increased dry static stability (changes in lapse rate of temperature), it is the reverse for CAPE: convective available potential energy) when moisture is accounted for. CAPE increases and so more activity. But even this is complex because strong activity in one area necessarily creates changes in large-scale overturning (like monsoons) and while increased convection occurs in one region decreases occur elsewhere due to changes in subsiding air and wind shear (which can blow incipient vortices apart).

There are very poor or no decent stats on lifetime or size.

An example:

One somewhat unpredictable aspect of TCs is the eyewall formation and replacement. Because of the strong winds around the eye of the storm, the spiral arm bands wrap around and can shut off the flow of moisture into the original eyewall, causing it to die, and a new eyewall forms farther from the center. In the past, this process often led to the demise of the storm (e.g. Katrina), but nowadays the TC often recovers as a bigger storm and it spins up again. So it lasts longer and is bigger. Irma in 2017, underwent several eyewall replacements and got bigger and bigger and straddled Florida, and had a long life. It cost over $100M.

Should this count as one storm or 5? Numbers are meaningless without duration and intensity.

(See Trenberth, K. E., L. Cheng, P. Jacobs, Y. Zhang, and J. Fasullo, 2018: Hurricane Harvey links to ocean heat content. Earth’s Future, 6, 730-744, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF000825 .

Here is another non-sensical argument I saw for the first time today: “climate disaster costs are rising at a rate slower than GDP so it isn’t a problem.”

Set aside for a moment whether or not the statement is factually true, and you are left with we can “afford the cost” of climate disasters so what’s the problem?

People who do not want to see the elephant either because they deliberately close their eyes or are so short-sighted all they see is grey, will refuse to believe there is in fact an elephant in the room.