Revisiting the hot model problem

Despite a hot 2023 and the recent Hansen et al paper, there is still reason to doubt very high climate sensitivity models

In a recent YouTube video, the physicist and science communicator Sabine Hossenfelder brought up the “hot model problem” that one of us (ZH) addressed in a Nature commentary last year, and suggested that it might be worth revisiting in light of recent developments.

While 2023 saw exception levels of warmth – far beyond what we had expected at the start of the year – global temperatures remain consistent with the IPCC’s assessed warming projections that exclude hot models, and last year does not provide any evidence that the climate is more sensitive to our emissions than previously expected.

In this article we’ll explain a bit of the background of the hot model problem in CMIP6, how the community dealt with it in the IPCC 6th Assessment Report, and why we are still reasonably confident that we should continue to give hot models less weight in future warming projections.

The problem with hot models in CMIP6

The authors of the recent IPCC 6th Assessment Report faced a bit of a dilemma. On one hand, the recent generation of climate models (CMIP6) had recently been released and showed a notably larger range of climate sensitivity – how much the planet warms in response to increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration – with a number of models running much hotter and showing greater levels of future warming than those in the prior generation.

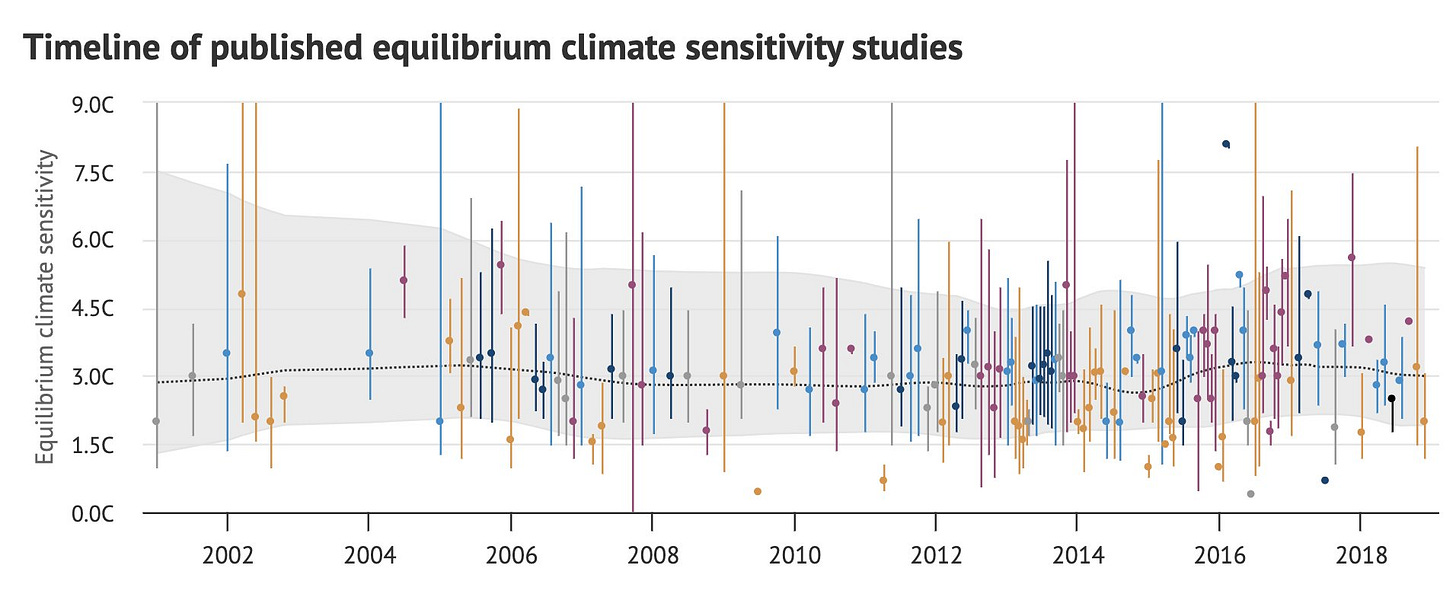

Around a fifth of the new CMIP6 models lie outside the very likely (90th percentile) equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) range adopted by the IPCC AR6, with 18% of CMIP6 models having an ECS above 5C per doubling CO2 and 27% of CMIP6 models having an ECS higher than the most sensitive model in the prior generation (CMIP5).

On the other hand, a sizable number of studies were being released suggesting that the very high sensitivity subset of new climate models did a poor job of reproducing historical temperatures, and those tested had trouble simulating the conditions of the last ice age.

A community review of climate sensitivity came out – Sherwood et al 2020 – using multiple lines of evidence from historical observations, paleoclimate proxy records of the Earth’s more distant past and physical process models to show that the range of climate sensitivity should be narrowed, not expanded.

To reconcile this new, narrower sensitivity range with CMIP6 models, the AR6 authors made a notable changes in their use of climate models relative to prior reports. They created “assessed global warming” projections that went beyond the simple model average used in prior IPCC assessments. The IPCC also increasingly chose to emphasize impacts as a function of global warming level as opposed to time.

However, these new assessed warming projections were produced by an approach – combining weighted CMIP6 models with a simple emulator tuned to the AR6 sensitivity range – that generated global average surface temperature series but did not provided gridded model fields needed to assess regional climate impacts.

To provide a resource for the community to effectively use CMIP6 models in a way consistent with AR6 assessed warming, we proposed screening CMIP6 models based on their transient climate response (TCR – effectively their shorter-term climate sensitivity), limiting the analysis to those CMIP6 models whose TCR fall within the IPCC’s “likely” range of 1.4C to 2.2C.

As shown in the figure below, this results in global average warming estimates largely similar to those produced by the IPCC’s assessed warming approach.

In her video, Dr. Hossenfelder suggests that the “hot models” include better physics of cloud behavior that can in turn result in more accurate short-term weather forecasts, citing a paper by Williams et al 2020 assessing HadGEM3 model (ECS 5.5C). However, other models that include updated cloud physics have lower climate sensitivity, and this one test does not obviate the other challenges facing high sensitivity models – their poor agreement with historical temperatures, their inability to reproduce the last glacial maximum, and their inconsistency with other lines of evidence constraining climate sensitivity.

The high climate sensitivity in Hansen et al

In a recent paper, Dr. James Hansen and colleagues made the case that climate sensitivity is on the high end of the very likely range in the recent IPCC report, at 4.8°C ± 1.2°C per doubling CO2. They justify this estimate based on recent estimates of glacial-to-interglacial global temperature changes from Tierney et al. 2020 and Osman et al 2021.

Hansen et al. may well be correct; its quite possible that climate sensitivity to be 4.8C, as its within the “very likely” (90th percentile) range of 2C to 5C that we suggest in Sherwood et al 2020.

However, its worth putting the Hansen’s estimate into context; there are dozens of different studies of climate sensitivity published each year using different approaches. A few days before Hansen’s paper a separate estimate by Cropper et al 2023 using climate variability found that climate sensitivity is 2.8C ± 0.8C. The Tierney et al paper that Hansen et al rely on itself finds a best estimate of climate sensitivity of 3.4C (2.4C–4.5C). And a new preprint by many of the paleoclimate experts that Hansen et al rely on (including Tierney and Osman) uses the last glacial maximum to argue for an ECS of 2.9C (2.1C–4.1C).

Given all the conflicting estimates, I'd strongly advise folks against glomming onto any single new study (particularly if it informs ones priors that sensitivity is high or low). Instead, we should synthesize all the different lines of evidence, as was done in both Sherwood et al 2020 and the recent IPCC report. Across hundreds of different studies, and our best estimate remains somewhere between 2C and 5C.

The impacts of climate change

Dr. Hossenfelder also talked about the impacts of climate change and her analysis here is on much firmer ground. As the last IPCC report said,

With every additional increment of global warming, changes in extremes continue to become larger. For example, every additional 0.5°C of global warming causes clearly discernible increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes, including heatwaves (very likely), and heavy precipitation (high confidence), as well as agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions (high confidence).

These changes can play havoc with agriculture (despite people saying “CO2 is plant food”), fresh water availability, and many other aspects of the human system. We also know that climate change is already killing people — millions of people over the last 20 years. This will only get worse, possibly rapidly. How much worse, no one knows, especially economists.

In response to rapid climate deterioration, people will do what they’ve always done: migrated. Such massive movements of people will strain resources, challenge political systems, and foster social tensions. Given the intense U.S. political debates over immigration and borders, it is clear that this will be profoundly disruptive to our society.

Conclusions

Arguments over ECS are distractions. Whether it’s 3C or 5C is a bit like whether a firing squad has 6 rifleman or 10. It’s bad either way. Ongoing research will continue to sharpen our understanding of ECS, but it won't change the immediate task before us: the rapid decarbonization of our society. This remains our paramount challenge, regardless of the precise severity of the climate threat.

Related posts

Even a one rifleman firing squad is pretty bad when you think about it.

And thinking about it that way would have been a good idea back in the 1990s. Sigh.

Economists are rarely humorous but a dead clock is right twice a day, that is if you're old enough to know what an analog clock is. Economists say predictions are difficult, especially about the future. There is an overabundance of evidence that we have had a considerable over-reliance on modeling. And when combined with the maximal conservatism of scientific paper publishing language, vs using actuarial principles to convey risk analysis to the public and policy makers, the result is we are heading into rougher waters faster than we are prepared for. While I appreciate the complicated nature of this topic (modeling) I must admit that I find any discussion of whatever the F the IPCC does, says, averages, models or fingers to be a complete violation of rational analysis, given that the IPCC is a politically driven vehicle, not a science based arbiter of truth. And my sincere apologies for using the word truth in this (or any) context but I didn't want to spend too much time overthinking this absolutely inconsequential and utterly irrelevant reply. I used to think that our societies will collapse, if by climate change, due to solving it was not economically profitable enough. Then I started thinking that we will more likely succumb to the inevitable regulatory blockades without enough time to unravel the contradictions in our man made paradigm. Lately I've been thinking that it may be we've spent too much time averaging the model results in an effort to comfort ourselves. I'm voting for Massive Asteroid 2024 for President, campaign slogan: Not Soon Enough. Sorry. Sh*t got dark all a sudden. :/