Keep it in the ground?

When the politics of affordability meet the needs of climate mitigation

Recently there has been quite a debate online about the extent to which opposing near-term oil and gas infrastructure – pipelines, refineries, new production – is both necessary and politically effective as a strategy to reduce US emissions. These conversations have occurred in the context of a broader pivot toward affordability as a rallying cry of the left in the US, driven by concerns around the rapidly rising cost of housing, energy, and other goods.

Matt Yglesias had a provocative piece in the NYT arguing that liberals should be less opposed to oil and gas, arguing that it might help make energy more affordable and win more conservative states and labor (without which there would be no climate policy at all). He also noted that US oil and gas is generally lower carbon than foreign alternatives in a world that is still using vast amounts of the stuff. Policies, in his view, should focus on making production cleaner by more strictly regulating methane emissions, in-sector electrification, and other best practices rather than restricting supply. Other mitigation advocates like Jesse Jenkins and Ramez Naam chimed in to support the broad thrust of his argument.

This is, it is worth pointing out, not too far from the policies pursued by both the Obama and Biden1 administrations, where both clean energy and domestic oil and gas production boomed (while the dirtiest fossil fuel, coal, saw a dramatic decline).

Representative Sean Casten (D-IL) posted a long rebuttal on BlueSky arguing that we’ve already overshot our climate goals, and the only way to turn things around is to keep fossil fuels in the ground. He noted that what is politically popular is not always what is right, and that sometimes politicians need to do what is necessary to meet the moment. He also notes that leakage from US gas “makes natural gas worse than coal from a global warming perspective.”

These responses broadly reflect two different schools of thought on how to best practically (and politically) achieve decarbonization goals: by reducing fossil fuel supplies, or by reducing fossil fuel demands.

The physical science is absolutely clear that to stop the world from warming we need to get global emissions of CO2 and other long-lived greenhouse gases to (net) zero. Every 220 gigatons (billion tons) of CO2 we emit warms the surface by around 0.1C, and the world is already at 1.4C above preindustrial levels today. But the specific path to limit warming – how much we focus on the reducing the supply of fossil fuels vs reducing their demand by accelerating the adoption of cleaner alternatives is very much an active debate. My personal view is that demand side policies are considerably more achievable at the moment – particularly given the new focus on affordability on the left.

I’d also note that this post is about the politics of mitigation rather than the physical science. There is no clear right answer to how to best reduce emissions, and there are many reasonable folks with differing views on the topic. We should generally try and extend grace to those we disagree with, as when it comes to policy there is no real arbiter of truth.

Demand vs supply-side decarbonization

Broadly speaking, there are two different schools of thought on how to best achieve decarbonization: supply side vs demand side policy.

Supply side policy focuses on making fossil fuels more expensive by restricting the supply or directly taxing the their sale. Examples include restrictions on fossil resource leasing and development, blocking transmission systems like pipelines, cap and trade systems, and carbon taxes.

Demand side policy aims to make cleaner alternatives more affordable and, in turn, reduce demand for fossil fuels. This generally involves subsidizing both the research, development, and deployment of clean energy technologies (renewable energy, nuclear, electric vehicles, heat pumps, etc.) and its supporting infrastructure (transmission, vehicle charging infrastructure)

These are not necessarily mutually exclusive; for example, some advocates of demand side interventions also support carbon taxes. But generally speaking, supply side policies impose more direct costs on consumers, while demand side policies involve more indirect costs (e.g. through higher government spending).2 There are also ways to make supply side policies less costly – such as the revenue neutral carbon taxes that Canada and Washington have experimented with – but even these have been hard to muster political support for.3

Most of the policies pursued by the Biden administration (and the Obama administration before it) have focused on demand-side mitigation policy. While we may wish otherwise, most of the general public in the US does not prioritize climate change above economic issues, and in the past when gasoline prices have spiked some politicians have quickly pivoted from “keep it in the ground” to “drill baby drill”. To be effective in changing consumer and commercial purchasing behavior at the scale needed to avoid dangerous levels of warming this century, supply side policies will necessarily need to impose a level of cost that will be politically challenging (to say the least).

Demand side mitigation can effectively reduce fossil fuel emissions. The large-scale phase down of coal in the US was driven by a combination of stricter conventional pollutant restrictions and – primarily – low cost fossil gas4 and renewable generation that made it not economically competitive.5 More broadly, the Global Carbon Project finds that emissions have declined over the past decade (2015-24) in 35 nations, which collectively account for 27% of global emissions, driven by faster installation of clean energy technologies and the retirement or curtailment of existing fossil fuel resources. This remains true even when emissions embodied in international trade are taken into account.

The challenge with demand side policies is that they are arguably a poor fit for meeting our most ambitious global climate targets. If countries want to limit warming to 1.5C by the end of the century (and minimize overshoot on the way there) it leaves us with a vanishingly small carbon budget. To meet these goals would require wartime style mobilization of the world to rapidly decarbonize, prematurely retiring vast amounts of infrastructure and rapidly curtailing fossil fuel production. In short, it would cost a lot of money – and in turn require significant political and public buy-in.

Is 1.5C increasingly a trap?

The 2015 Paris Agreement set an aspirational target of limiting warming to 1.5C. This came as a bit of a surprise to the climate science community; prior to Paris the most ambitious mitigation scenario that was widely modeled was RCP2.6, which limited warming to around 1.8C by 2100 (and had a ~66% chance of avoiding 2C warming). Following the Paris Agreement the UNFCCC requested that the IPCC write a special report on 1.5C as a climate target, which was published in 2018.

By the time that report came out, it was increasingly clear that actually limiting warming to 1.5C would be quite unlikely, with scenarios that avoided overshoot requiring all global emissions to start declining immediately and reach (net) zero emissions by 2050. By the time the IPCC 5th Assessment Report was published in 2021, the 1.5C target has been quietly redefined as an “overshoot” target where the world passed 1.5C before bringing global temperatures back down through large-scale deployments of net-negative emissions. In that report 206 of 230 the integrated assessment model (IAM) scenarios exploring 1.5C warming outcomes – a full 96% – involved overshoot on the way there, often reaching 1.7C or 1.8C by mid-to-late century.

As 2026 dawns, the world has already seen a year above 1.5C, and global emissions have yet to decline (even if they have plateaued), scenarios that limit warming to 1.5C by 2100 have become increasingly implausible. They are forced to rely on ever more rapid near-term emissions reductions – and ever larger amounts of carbon removal later in the century – to make the brutal math of the 1.5C target work.

For this reason many of us in the scientific community have been trying to make it clear that these targets never reflected a climate threshold – a point in the system where something particularly bad happens. Rather, they reflect an attempt to balance minimizing climate damages (and risks) given what is plausibly achievable. Climate targets are always inherently probabilistic given uncertainties in climate sensitivity and carbon cycle feedbacks. Its quite possible that we could end up closer to 3C even though we thought we were heading to 2C if we roll 6s on the proverbial climate dice. So these targets more about minimizing tail risks than ending up at a particular round number.

Similarly, there are no particular climate feedbacks or tipping points that occur at 1.5C that would not occur at 1.45C or 1.55C; rather, we try to emphasize that every tenth of a degree matters. 1.5C is lower risk than 1.7C, which is lower risk than 2C, etc. Its less “1.5C to stay alive” and more that we should try to mitigate as rapidly as practically possible to reduce the future damages to society and the natural world.

While targets can be useful as a focus for pushing countries to adopt more ambitious mitigation policy, they can also become counterproductive if they are unachievable. For example, a narrow focus on 1.5C today could lead folks to advocate to oppose policies that might be consistent with (or even help enable) a 2C world but would not be consistent with the vanishingly small remaining carbon budget under 1.5C. In other words, pursuing our most ambitious targets can lead us to make the perfect the enemy of the good.

The gas debate

In the US context the distinction between policies that would be inconsistent with a 1.5C world but might help us get close to 2C often involve fossil gas. The climate impacts of gas (and how it compares to coal) is a topic I’ve long been interested in; I published my first analysis back in 2011, and ultimately wrote two peer reviewed papers on the topic in 2015 and 2016 looking at the impacts of replacing coal with gas in the US.

This is relevant because in the US fossil gas has been the single largest driver of CO2 reductions, particularly in the power sector. Along with renewables it has led to a reduction of coal use by 60%. This progress remains fragile, as may coal plants have lowered their operation time (their capacity factor) rather than fully shutting down, and we see an uptick in US coal generation whenever gas prices rise.

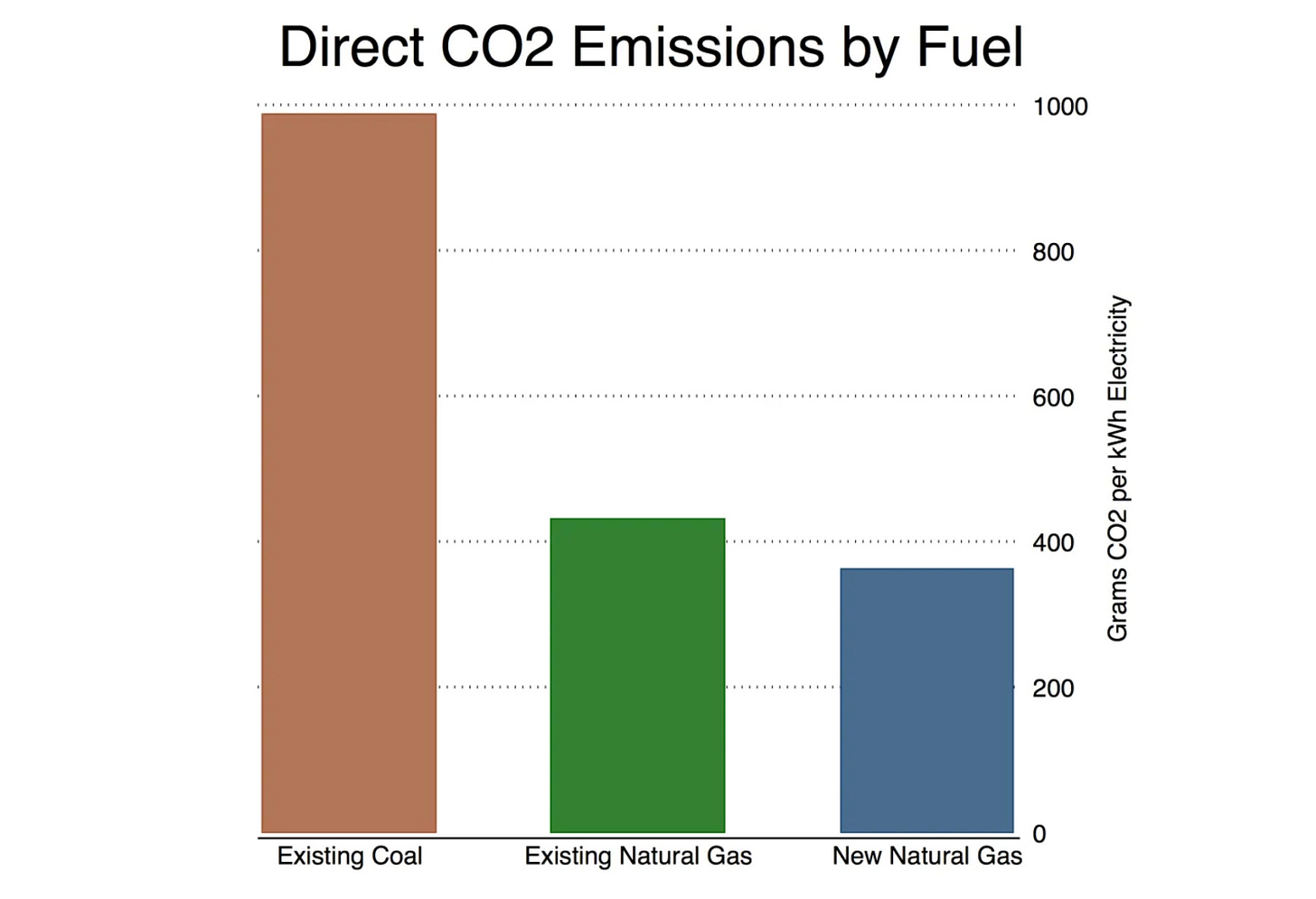

From a carbon standpoint the comparison is relatively straightforward. Fossil gas is results in about 60% lower CO2 emissions per kWh generated, as shown in the figure below:

However, there has been quite a bit of controversy around the broader climate impacts of fossil gas, given that a portion (likely 2% to 3%)6 of fossil gas leaks as methane. Methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas with a lifetime of around 12 years in the atmosphere, but while it is in the atmosphere it has approximately 120x more warming impact than CO2. The different lifetime of the gases makes it difficult to directly compare the two, given that the results depend on the timeframe considered.

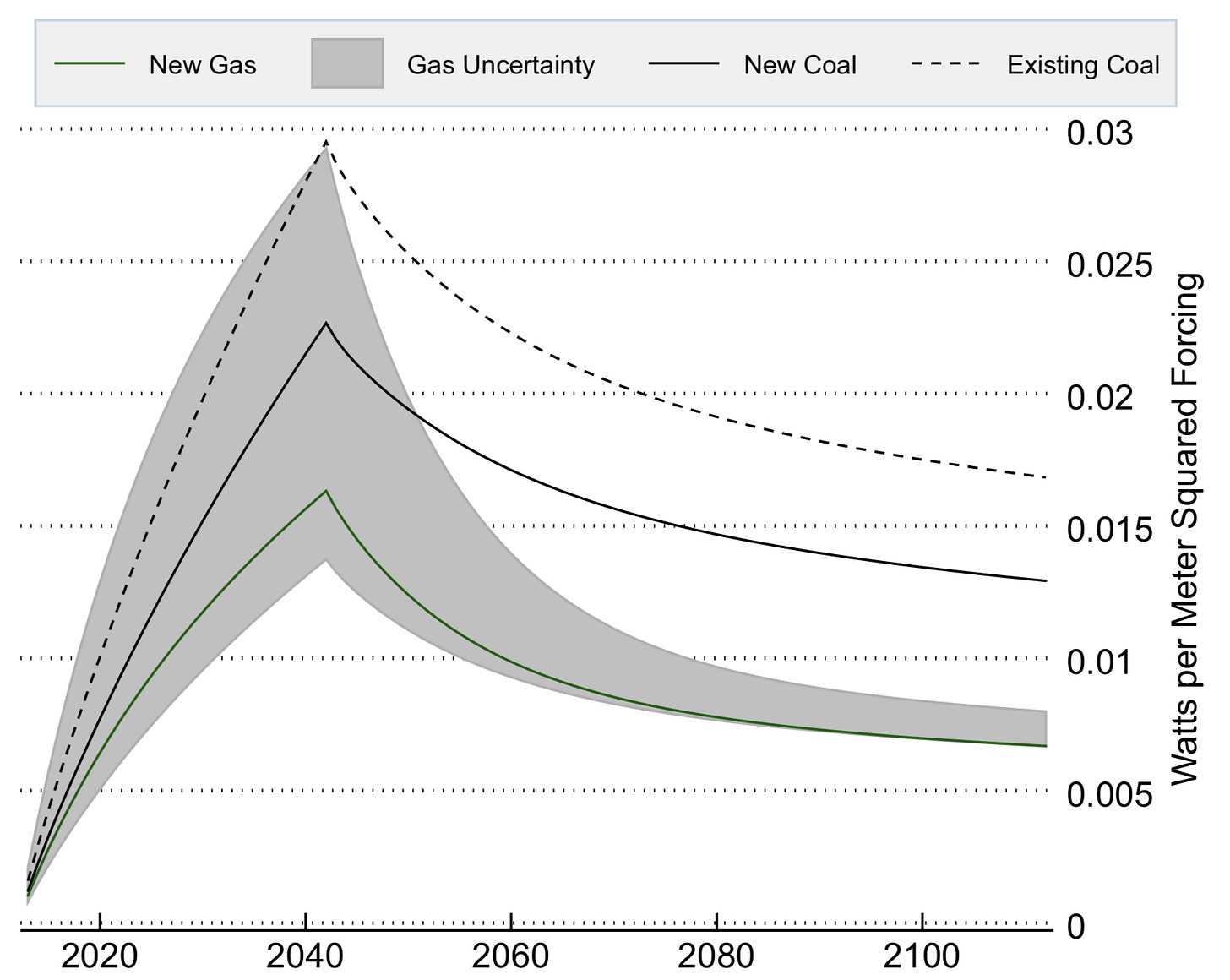

The figure below (from my 2015 paper) attempts to compare gas and coal climate impacts over time, using the change in radiative forcing of both (which is a reasonably proxy for temperature change). It compares a new gas plant in the US with 2% leakage (green line) to both new coal (black solid line) and existing coal (black dashed line). The grey area represents the uncertainty for gas across leakage rates from 1% to 6% and generation efficiencies (HHV) of 42% to 50%. This plot assumes that both the gas and coal plant would be operated for 30 years before being retired.

This implies that a leakage rate of 5.1% would be required to make gas worse than coal over a 20-year period (assuming new gas displacing existing coal – the most common occurrence) and 13.1% over a 100-year period. If we assume the gas and coal plants would both be operated for 100 years rather than just 30, the leakage rate required for 100-year forcing parity falls to 9.9%.

Some folks argue that a 20-year time horizon should be preferred given the near-term impacts of climate change and the risk of passing tipping points. But in my view such a short time horizon is misguided. Its equivalent to discounting the future by around 13% per year – saddling future generations with higher warming from CO2 in exchange for minimizing near-term warming today. The case for 20-year GWPs to avoid tipping points is also fairly weak; most proposed tipping points depend on the level of peak warming and the timeframe over which it is sustained. It is quite unlikely that the world will reach peak warming before 2070 or 2080 even in ambitious mitigation scenarios, which means that little of the methane emitted today will be warming the planet by then.

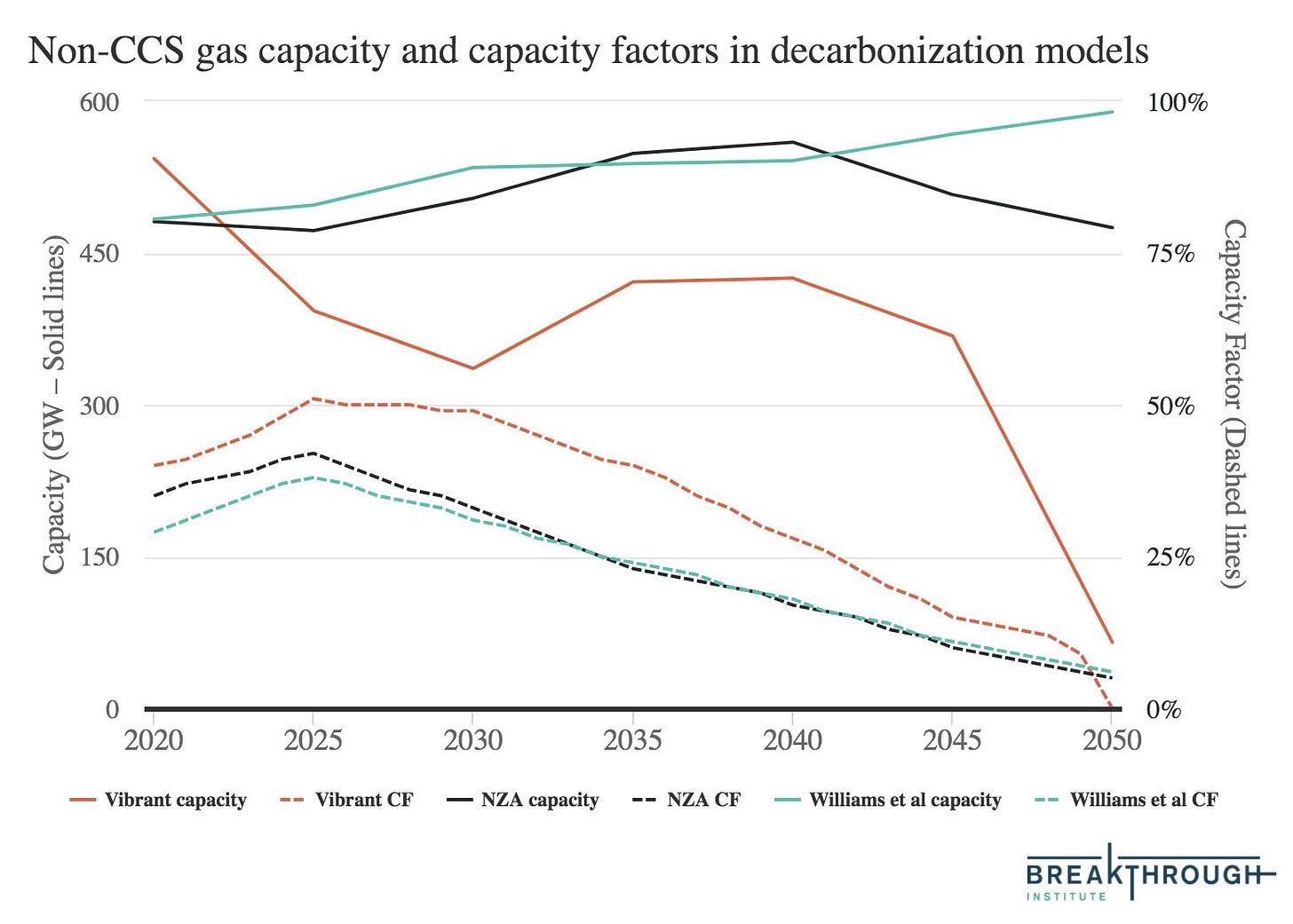

Of course, the argument that gas is“worse than coal” is an unnecessarily high bar in a world that needs to get to net zero emissions. But gas displacing coal is generally still a good thing today, provided there are no other viable cheaper options. Gas also is something of a Swiss army knife of the electricity system, able to be built quite cheaply but expensive to operate (e.g. low cap-ex and high op-ex). This makes it quite well suited to be a dispatchable resource; cost effective to shut down during periods when cheap renewable or battery storage is available, and able to run when extended low resource outputs makes it necessary. That is one of the reasons why deep decarbonization scenarios for the US generally have considerable amounts of fossil gas capacity remaining in a net-zero system in 2050, even if utilization rates are quite low (~5%).

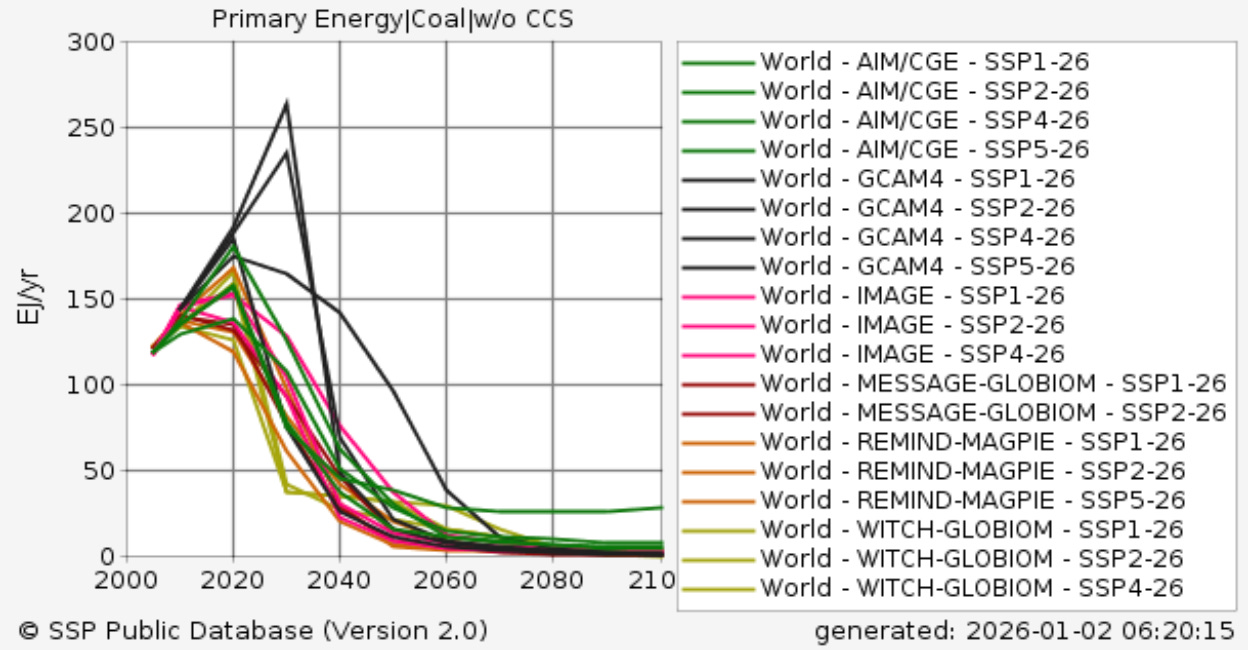

More broadly, integrated assessment models used by the IPCC to assess mitigation options have a pretty clear “merit order” for phasing out fossil fuels: coal first, than oil, than gas. For example, here is unabated (without CCS) coal use in 2C scenarios (SSP1-2.6) in the SSP Database used in the IPCC 6th Assessment Report, showing rapid declines in global coal use after 2020 (something that, unfortunately, we have yet to see globally in the real world).

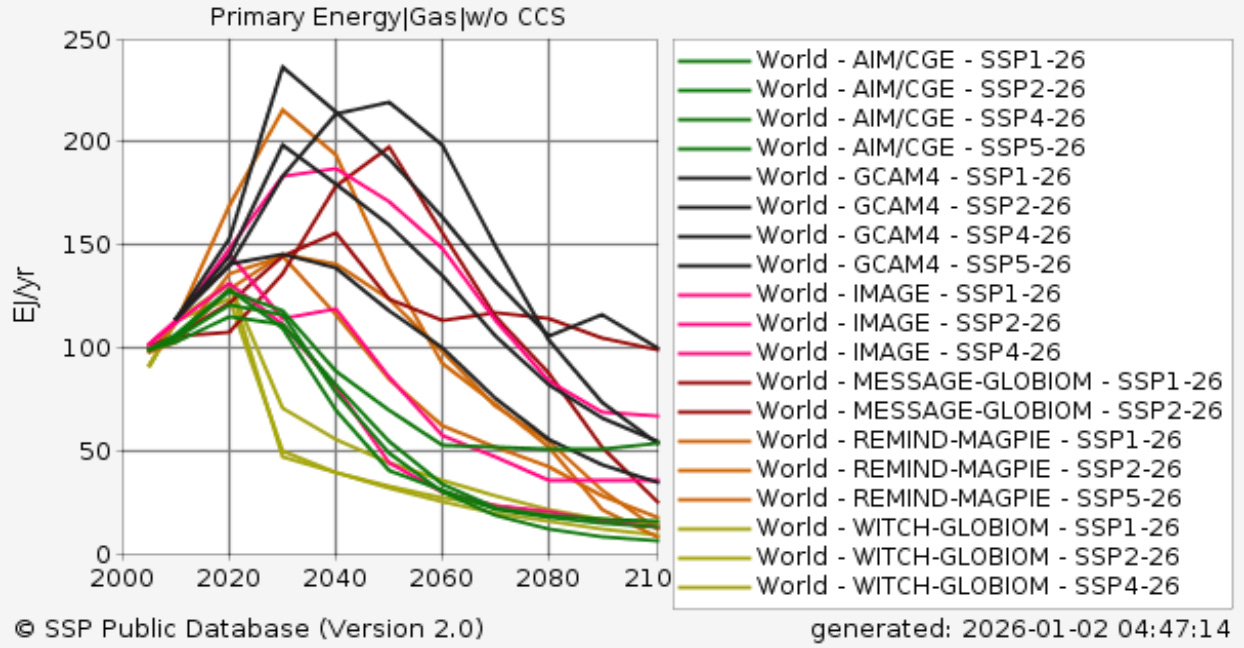

Global unabated gas use is more of a mixed picture, with some models (WITCH) showing rapid declines but others showing flat (AIM) or even increasing (GCAM, MESSAGE, REMIND) global gas use through 2030 or 2040.

As clean energy alternatives – particular solar and batteries – get cheaper they should undermine the economic case for fossil gas and help drive down usage and emissions. But in my view policies to restrict supplies today will be less effective than accelerating the deployment of more cost-effective alternatives to gas.

Its the (political) economy

Effectively mitigating climate change will depend on a combination of technology and policy.7 But we live in a world where policy and politics are the art of the possible, and given the increasing focus on affordability it seems like a focus on making clean energy cheap will be considerably more viable than making fossil fuels more expensive. As Yglesias noted in the Times, for the Democrats to retake power and control the Senate requires winning places like North Carolina, Ohio, or even places like Texas, Alaska, and Kansas.

I do disagree with Yglesias that the left should actively “support” the oil and gas industry, but there are a wide range of effective mitigation policies that we can pursue that make clean energy cheaper without supporting or directly penalizing the oil and gas industry. I also think we need to double down on phasing out coal as rapidly as possible, both domestically and overseas.

This means that there is likely still some role for supply side mitigation, particularly in a world where demand side mitigation is succeeding. As demand for oil and gas peaks and declines, the cost of these fuels will fall, potentially undercutting the economics of cleaner alternatives. One option would be to effectively backstop the price of oil and gas with a carbon tax – at least up to an estimated social cost of carbon. This would have the advantage of helping stabilize fuel prices, and consumers would not experience any cost increases (though they would not benefit from declines).

Similarly, there are other non-climate damages associated with fossil fuel use – air pollution and water pollution – that also merit regulation, and restrictions on mercury, sulfur, and other conventional pollutants have played an important role in retiring coal plants in the US by making coal more expensive to operate. There is an important role for the government in regulating these – as well as implementing stricter restrictions on methane leakage. And it should go without saying that we should oppose the types of direct subsidies or mandates around fossil fuels or restrictions on clean energy production that tilt the playing field toward dirtier energy that the current US administration is pursuing.

Ultimately the costs of fossil fuel use need to be reflected in the costs of energy for decarbonization to succeed, and this can occur either through artificially reducing the cost of clean energy or increasing the cost of dirty energy. At the current political moment, the former seems far more likely to work.

I’d be grateful if you could hit the like button ❤️ below! It helps more people discover these ideas and lets me know what’s connecting with readers.

Outside of the short-lived Biden era restrictions on oil and gas leases on federal land, which were ultimately thrown out by the courts and were mostly symbolic given the relatively minor amount of production occurring on federal lands.

Economists will point out that taxing the bad is generally more efficient than subsidizing the good, all things considered, but (and apologies to economists in the audience) what is most economically efficient is not necessarily the most politically palatable in practice.

Canada’s carbon tax was more or less repealed in 2025, while Washington state’s tax has also struggled to get popular support at times.

I prefer the term fossil gas to natural gas, as “natural” is a weird anachronism originally used to differentiate geologically produced (e.g. natural) gas from gas produced from heating coal (“town gas”).

Though we don’t live in a purely economically-driven world; local activism such as the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign helped convince policymakers to prematurely retire plants in favor of lower cost cleaner alternatives.

Estimates in the academic literature are that actual leakage is around 50% to 100% larger than the ~1.5% that the EPA reports in official inventories.

And its worth noting that technological progress is not independent of policy, given the key role of government spending in RD&D.

How dare you find a middle ground...

great contribution, Zeke!

I find myself like Jesse with MY - "98% agreeing!"

I tend to disagree on your categorization that a price on carbon is (primarily) supply side rather than demand side. other than changing the input costs to fossil fuel supply (steel, cement, on and on) most of the effect - and, as far as I understand, assumed so by economics - is on the demand side and switching at the margin there (which does have knock-on effects on investment decisions for supply).

that still leaves the political economy of carbon pricing as an open question - as you do a good job of highlighting!

positioning it as a backstop may be a best-possible approach at some point... the case remains that it is still likely the most "efficient" mitigation tool in the theoretical toolkit. whether we ever reach for it, who knows? need to press on the levers that are working now, unless and until that day comes.🤷