Emissions are no longer following the worst case scenario

So where might we be headed instead?

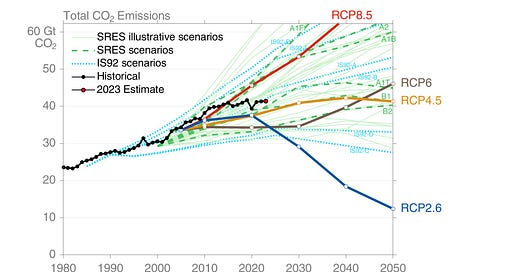

If you step back in time to 2014, global CO2 emission told a pretty frightening story. Emissions had rapidly increased at a rate of 3% per year in the 2000s, and there was not much sign yet of a slowdown in the early 2010s. Global emissions appeared to be following the worst case (RCP8.5) scenario.

But over the last decade things have started to change.

Global CO2 emissions (both fossil and land use) have been relatively flat during the 13 years after 2010, and are now closer to the middle-of-the-road RCP4.5 scenario than the high-end RCP8.5 one1. This is even more clear if we look at fossil CO2, which is the most important factor in long-term growth (as its responsible for 90%+ of future emissions in high-end scenarios).

This is due to the rapidly accelerating energy transition driven by falling costs of clean energy technologies, that has led to a stagnation of global coal use. The world spent $1.1 trillion dollars on clean energy technologies in 2022, up from around $780 billion in 2021 and $600 billion in 2020, a trend that shows no sign of slowing down.

Even more importantly, there is a growing consensus in the literature that global emissions are likely to remain flat even in the absence of strong climate policies enacted by countries. The figure below is from the IPCC 6th Assessment Report Synthesis, and shows the range of assessed current policy projections for global CO2 emissions in red (along with a somewhat arbitrary selected marker scenario in with a solid red line).

Implications for future warming

What does this flattening of emissions and divergence from the high-end scenario mean for the climate going forward? First, its important to emphasize that a flatting of emissions does not mean that global warming will stop or the problem will be solved. The amount of warming the world experiences is a function of our cumulative emissions, and the world will not stop warming until we get emissions all the way to net-zero. Even after we reach net-zero emissions, the world will not cool back down for many millennia to come in the absence of removing more CO2 from the atmosphere than we emit.

This is the brutal math of climate change, and the reason why its so important to start reducing our emissions quickly. We are already well off track for what would be needed to limit warming to 1.5C without large overshoot (and the need for lots of negative emissions to bring temperatures back down). If we do not start reducing global emissions over the coming decade, plausible scenarios to limit warming to below 2C will move out of reach as well.

Second, its important to note that emissions are only one of three sources of uncertainty when we try to assess out how much the climate will warming this century. The other major factors are how sensitive the climate is to our emissions – the combination of various physical processes that amplify warming from greenhouse gases, such as increased evaporation, changes in cloud formation, or melting snow and ice – as well as how the carbon cycle responds to our emissions and how that affects the ability of the Earth to take up a portion of what we emit.

The figure below provides a visual summary of these different uncertainties based on estimates in the literature.

This figure shows warming through 2100, but its important to note that the world does not end in 2100 even though most of our model runs do. As long as CO2 emissions remain above zero, the world will continue to warm indefinitely.

That being said, its clear that a reassessment of likely future emissions has notably lowered the range of likely temperature outcomes over the next century. The figure below shows recent assessments of likely temperature outcomes this century under three different scenarios:

Current policies - where policies in place today are maintained and trends in declining clean energy costs continue, but no new policies are enacted.

2030 commitments - where countries meet their 2030 nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement but enact no new policies after that.

Net-zero pledges - where countries meet their stated commitments to reach net-zero (e.g. in 2050 for the US and EU, 2060 for China, 2070 for India).

These estimates come from three different groups: the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP)’s 2022 Emission Gap Report (shown in red), the Climate Action Tracker (shown in blue), and the International Energy Agency’s 2022 World Energy Outlook (shown in yellow).

These future warming projections under current policy broadly align with the SSP2-4.5 scenario in the most recent IPCC 6th Assessment Report (grey bars), and are well below the no-policy baseline scenarios (SSP5-8.5 and SSP3-7.0).

In a recent piece in the journal Nature, Fran Moore and I assessed the literature on current policy, 2030 commitments, and net-zero pledges more broadly. The figure below shows our assessment of likely warming over the next century (red area) across these different scenarios compared to the full range in the IPCC AR6.

You can see all the individual studies that went into this assessment in the figure below (which has also been updated to include the new van de Ven et al 2023 study), The figure shows both the range of future emissions uncertainties in each study as well as full range of temperature outcomes that include climate system uncertainties.

So what should our takeaway from all of this be? First, there is some good news here. The world is no longer heading toward the worst-case outcome of 4C to 6C warming by 2100. Current policies put us on a best-estimate of around 2.6C warming.

At the same time, a world of 2.6C by 2100 is still a giant mess to leave to the future, including today’s young people, who will live through that, and warming continues after 2100 in these current policy scenarios. Climate system uncertainties mean that we could still end up with close to 4C warming if we get unlucky with climate sensitivity and carbon cycle feedbacks.

Its also important to emphasize that current policy scenarios represent neither a ceiling nor a floor on future emissions. While we’ve seen a ratcheting up of policy in the past, we can’t preclude a world that backslides on both current commitments and policies, increases subsidies for fossil fuels, or otherwise leads to higher future emissions than we expect.

Ultimately, the progress we have made should encourage us that progress is possible, but the large and growing gap between where we are headed today and what is needed to limit warming to well-below 2C means that we need to double down and light a (carbon-free) fire under policymakers to ratchet up emissions reductions over the next decade. Flattening the curve of global emissions is only the first step in a long road to get it all the way down to zero.

Really interesting, thank you. And encouraging too. This kind of thing - seeing that there is some change in the right direction - is important to communicate, especially when people are getting demoralised at the rate of progress. We are moving too slowly, but at least we can see the movement now.

You seem to be ignoring that methane emissions are rising fast, particularly due to melting permafrost, and with other greenhouse gases and atmospheric humidity, are accelerating the speed of climate changes.

You also seem to be ignoring that both forests and now oceans seem to have become net sources of carbon rather than carbon sinks, which must fundamentally affect the models you are referring to.

I also note that oil and gas exploration budgets have increased in many countries, China is actually increasing its coal production, and Britain has opened up new coal mines and North Sea oil and gas production.

If Trump takes the US presidency in the next few days, then the situation will suddenly become much worse. "Drill baby drill!"

There is also the likelihood of a Middle East war, in addition to the Ukraine war, both in oil and gas producer countries and, as always, wars contribute massively to CO2 emissions.

None of which suggests future CO2 emissions are under control.

And you don't mention the potential (and perhaps already underway) AMOC turnoff that'll also make your model's outcomes fundamentally irrelevant, at least in the Atlantic, Europe and the Artic.

As all the above seem outside your modelling, it seems hard to accept your analysis and proposed outcomes.