A truly worst-case climate scenario: Losing control of the carbon cycle

The consequences of human-induced climate change are becoming increasingly evident, as atmospheric CO2 levels continue to rise due to our relentless emissions. At present, we control CO2 emissions, but what happens when we lose that control?

Scientists have long speculated about the potential for warming to trigger feedback loops that release even more CO2 and methane into the atmosphere, amplifying the warming due to humans. David Wallace-Wells NYTimes climate newsletter talks about this with respect to the forest fires in Canada.

The dreaded carbon-cycle feedback loop

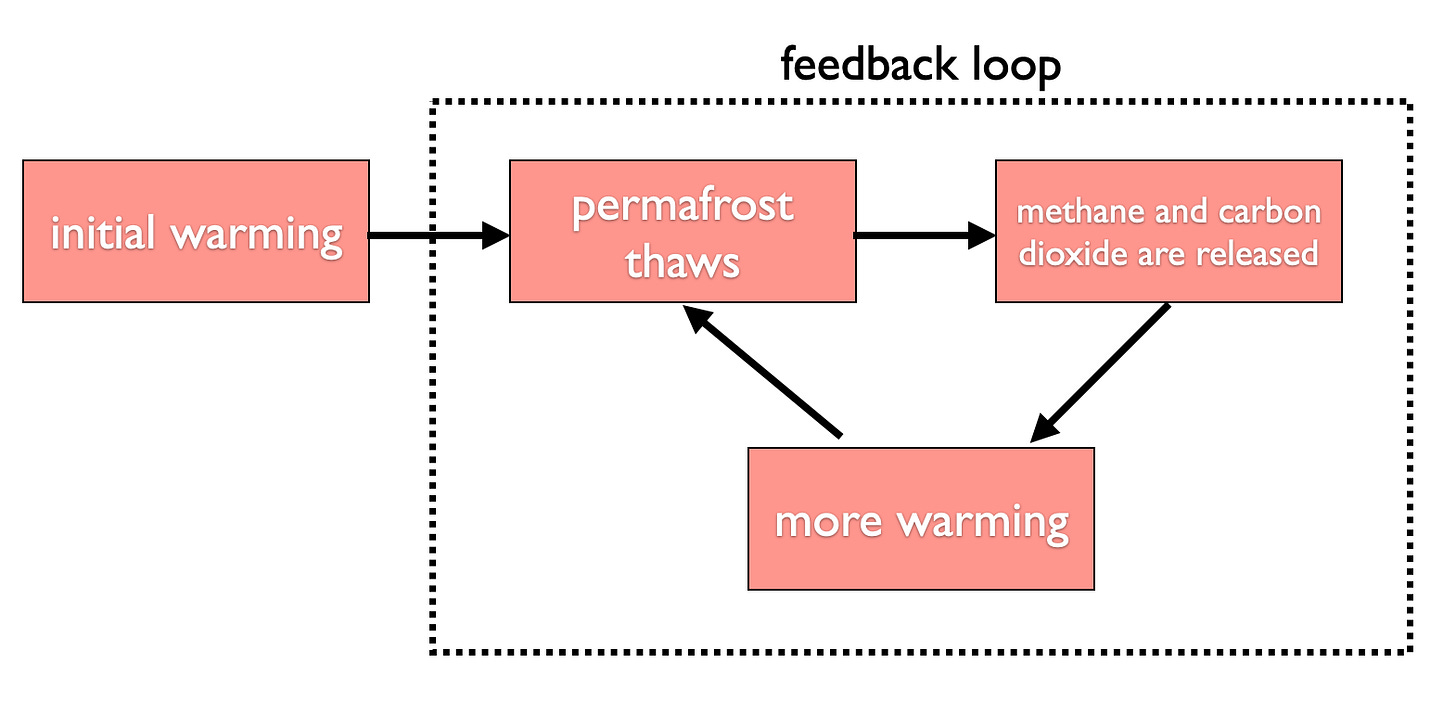

As the climate warms, natural processes can begin driving huge amounts of CO2 and methane emissions. For instance, warming temperatures can thaw permafrost, which holds vast amounts of organic carbon, like dead plants and the occasional woolly mammoth.

As this material thaws, bacteria would begin digesting it, releasing this stored carbon as CO2 or methane. The released gases, in turn, further contribute to warming, leading to more permafrost thawing and emissions, and thus, a vicious cycle ensues. This phenomenon is known as a carbon-cycle feedback loop:

As Wallace-Wells pointed out, the forest fires in Canada are emitting huge amounts of carbon, leading one to speculate on a forest-fire-feedback loop: warming temperatures promote more fires, which burns biomass, releasing carbon into the atmosphere, which drives more warming. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Another cause for concern lies within the soils of the Amazon rainforest. Observations in the last few years indicate that warming and deforestation have pushed some parts of the Amazon into becoming a net carbon source: in other words, they're releasing more carbon into the atmosphere than they’re absorbing. This net release of CO2 will drive additional warming, leading to more emissions from the Amazon.

Losing control of the carbon cycle

What makes this so worrying is the prospect of losing control over the carbon cycle. Once carbon-cycle feedbacks become significant, atmospheric CO2 levels would continue to rise even if humans reach stop emitting CO2 to the atmosphere (i.e., reach net zero).

In that case, reaching net zero emissions would become drastically harder. Stabilizing the climate would require last-ditch approaches like solar-radiation management (injecting sulfur into the stratosphere to reflect a bit of sunlight back to space).

The good news

Scientists have studied this and have put a lot of carbon cycle feedback dynamics (permafrost, etc.) into climate models. The good news is that they still show linear warming in response to human emissions, up to quite high concentrations. Thus, they don’t provide evidence that we’re right on the edge of carbon-cycle feedbacks becoming important.

It should be emphasized, however, that climate models’ simulations of the carbon cycle are one of the most uncertain aspects of the models. We’ve never gone through a big carbon-cycle feedback event, so we don’t have data to evaluate and verify their performance. Thus, we have to take the lack of strong feedback in them as being encouraging, but not definitive.

The bad news

The bad news is that we know that these carbon-cycle feedbacks will eventually kick in. We've seen it in the past, during ice-age cycles, for example. The figure below shows temperature and CO2 over the past 400,000 years.

During these cycles, which are driven by changes in the orbital parameters of the Earth, temperature changes first, followed by enormous changes in CO2 — this is a carbon-cycle feedback.

We are rolling the dice

The exact threshold at which carbon-cycle feedbacks become significant remains uncertain and we really don’t know how close we are to reaching it. So it’s yet another climate scenario that’s low probability but very high consequence.

More and more of these seem to turn up every day. Just a few days ago people were talking about the collapse of the Atlantic Ocean’s overturning circulation as another potential worst-case climate impact.

While each of these worst-case scenarios has to be individually characterized as unlikely, there are so many of them that we should expect at least one of them to materialize if we continue rapidly warming the climate. This is why it’s so important for us to limit warming as quickly as possible.

Related posts

Thank you for the comprehensive article. Sadly though, I sense we are “whistling past the graveyard” in our hubris of control. In psychology, there is a well-documented tendency to imagine we have much more control over random outcomes than reality dictates.

Humans tend to be eternal, optimists even when there is no evidence to support such Pollyantics. Youmadmitmthatmyour data and models are speculations since we have no historical hard facts to rely on. Might this simply be an example of our collective “illusion of control” when we might be wiser to assume the worst-case scenario and embrace our likely doom?

Gestalt psychologist Fritz Perls started: “Nothing changes until it becomes what it actually is.” There is no silver bullet to slay the beast, no world governmental white knight coming to make us all behave and save the day. As we inch toward a world human population of 10 billion or more, the consequences will be increasingly evident and probably not in a tidy linear manner. Wisdom would dictate that we assume the worst-case scenario and make preparations erring on the side of caution. Reality may nat look anything like our rosy models and it would be nice to have a ‘plan B.’

Under the "good news" portion of this article you state that scientists have done a lot of modeling of methane feedbacks, etc and that it still shows a linear warming. I find this to be reductive and missing of the point, which in my view as an engineer, is this: the fact that climate change is a composite problem, a rather complex polycentric nonlinear system problem, the linearity of warming is much more of an input and not solely an output as implied by your statement. Linear warming can and will have many resulting, often cascading effects. The fact that the warming is linear does not mean the impacts of that warming are linear as well.

Further, have you ever and I do mean even once, read a scientific paper or article about a scientific paper that states: Climate Change Not As Bad As Previously Estimated....? In 15 years of reading scientific papers and countless articles, I have only seen a constant steady stream of the opposite. So whenever I hear scientists or journalists making claims from a position of 'fact from modeling' I do remind myself that we're all just doing the best we can. "All models are incorrect, but some are useful" is the phrase many scientists use to caveat their model findings.

So, no... linear warming is not good news. It is only part of a larger more complex polycentric nonlinear system.