The rapidly shrinking carbon budget

What the latest numbers imply for meeting our climate goals

The carbon budget is a simple way to assess how much we can emit before we are committed to passing global temperature targets like 1.5C or 2C. It emerged from the consistent linear relationship between cumulative emissions and warming, and has been revised many times over the years as our best estimates of historical warming, emissions, and projected future warming have changes.

A recent paper – Forster et al 2023 – provides the latest update to the global carbon budget, revising the values presented in the 2021 IPCC 6th Assessment Report (AR6) WG1 to account for emissions over the past few years (the AR6 budget was provided relative to January 2020), updates to the MAGICC climate emulator to more accurately capture recent observations, and an increased the estimate of the importance of aerosols, which are expected to decline with time, causing a net warming, and decreasing the remaining carbon budget.

As a result, the global carbon budget has shrunk. Back in 2021 the AR6 gave the remaining carbon budget for a 50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5C as 500 GtCO2 (or around 12 years of current emissions). Forster et al finds that – as of January 2023 – the remaining carbon budget for a 50% chance of 1.5C is only 250 GtCO2, or 6.3 years of current emissions. Given that global emissions are not expected to decline in 2023, this would amount to only 210 GtCO2 remaining at the start of 2024.

The change is even more stark if we look at scenarios that “likely” limit warming to 1.5C – e.g. they have a roughly 66% chance of keeping warming to 1.5C. In these scenarios there is only a carbon budget of 150 GtCO2 left at the start of 2023 (and ~110 GtCO2 at the start of 2024), or ~4 (~3) years of current emissions. This compares to the 400 GtCO2 budget that the IPCC AR6 reported back in 2021.

The target of limiting warming to well-below 2C is generally interpreted as a >66% chance of avoiding 2C warming by 2100. This implies a carbon budget of 950 GtCO2 at the start of 2023 (910 at the start of 2024) according to Forster et al, or 24 years of current emissions, compared to 1150 GtCO2 in the AR6. Finally, for a 50% chance of 2C the new carbon budget is 1150 GtCO2, compared to 1350 GtCO2 in the AR6.

Its important to note that the year that the budget is used up is not necessarily the year we expect long-term average warming to pass the respective climate target – particularly in the case of 1.5C. Because the remaining carbon budget accounts for projected reductions in both non-CO2 emissions and falling aerosols, we expect reductions in aerosol cooling will unmask some of the current warming in the future.

Translating the carbon budget into emissions scenarios

The figure below provides a simple example of what these carbon budgets would require reducing global CO2 emissions to limiting warming to 1.5C (with either a 66% or 50% chance) or 2C (66% or 50%). It assumes that emissions linearly decline to zero at the start of 2024, with the area under each curve (after 2024) equal to the remaining carbon budget estimated by Forster et al 2023. Its important to note that this figure includes no net-negative emissions – which most of the models featured in the IPCC report use to extend the date at which emissions need to reach net-zero.

Here we find that to meet our climate targets, global emissions would have to reach zero in:

1.5C with a 66% chance – 2030

1.5C with a 50% chance – 2035

2C with a 66% chance – 2069

2C with a 50% chance – 2079

Its clear that global emissions will not get to zero in 2030 or 2035, which means we will end up in a world of overshoot, where the only way to get global temperatures back down to 1.5C is by removing more CO2 from the atmosphere than we emit. However, even these overshoot scenarios quickly become implausible in the amount of negative emissions required if global emissions do not rapidly decrease and reach net zero by the 2050s (as in most IPCC WG3 1.5C scenarios).

While we are already quite close to 1.5C today – global warming to-date has been around 1.3C – there is still a ways to go until we get close to 2C. This means that the remaining carbon budget and required net-zero dates are correspondingly larger and further out, and its easier to imagine a world of net-zero by 2069 with no large-scale net-negative emissions. At the same time, if we continue to emit CO2 at current levels for another decade or so, than achieving well-below 2C (e.g. a 66% chance of avoiding 2C) will be as challenging as avoiding 1.5C is today.

We can also look at these simple emissions pathways in the context of our historical emissions. The figure below shows historical emissions of CO2 from both fossil fuels and land use change since 1850, alongside the future emissions pathways implied by the latest carbon budgets. All of the pathways to meet our climate targets imply reducing emissions in the future faster than we have increased them in the past – and in the case of 1.5C scenarios, almost unimaginably faster.

How these emissions scenarios have changed over time

The Carbon Budget is very much a moving target, as it will be affected by our ongoing emissions, reassessments of historical emissions, and updates to climate models, and changing assumptions around non-CO2 greenhouse gases and aerosols.

The figure below shows the old simplified emissions pathways associated with the AR6 WG1 report (dashed lines) compared to the new ones from Forster et al. In all cases, the net-zero date is sooner and slope of the curve is steeper than in the AR6 budgets.

We can also go further back in time (as I’ve been making these charts since 2019!) and compare how the carbon budgets have evolved over time. The figure below shows budgets for a 50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5C as of 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2023:

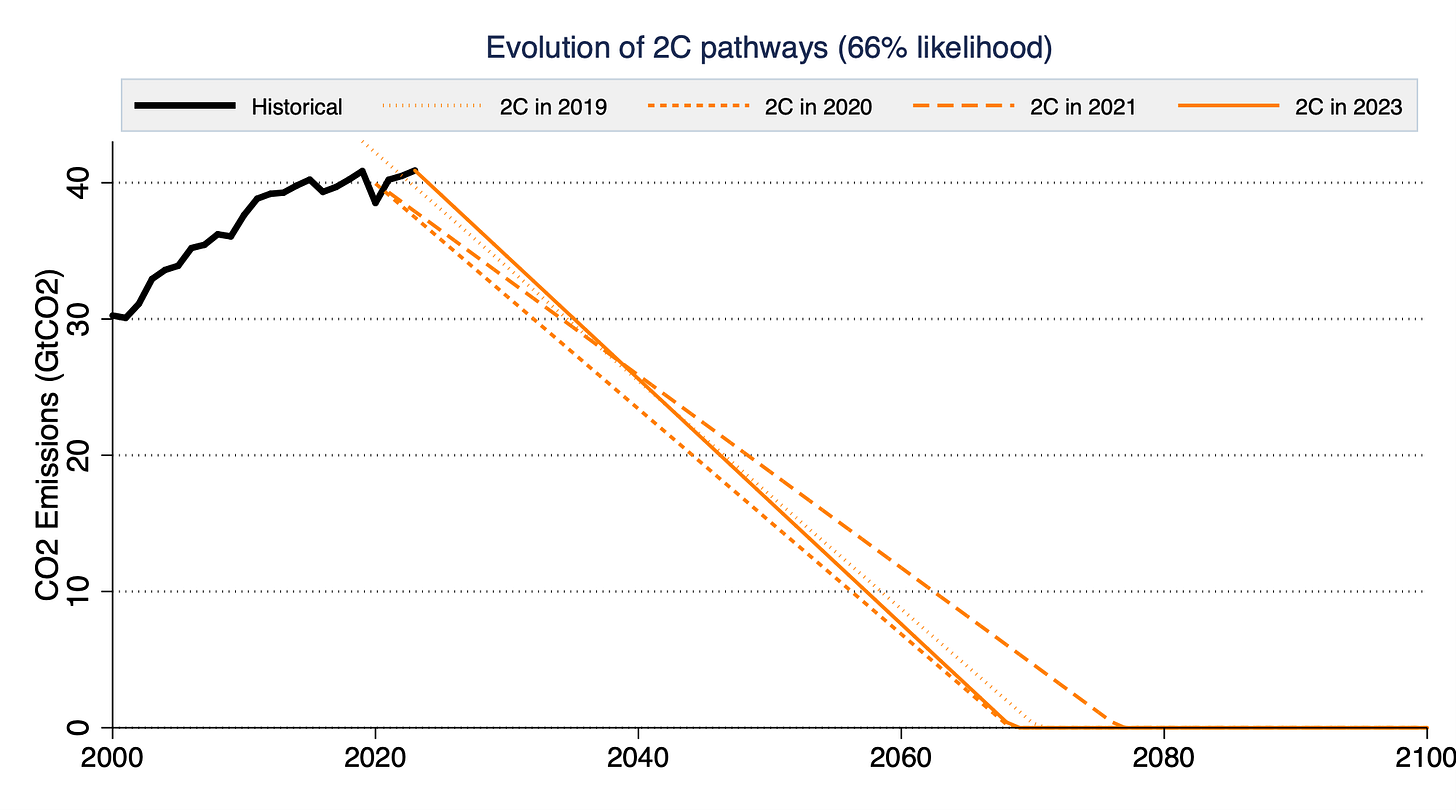

Similarly, here are budgets for a 66% chance of limiting warming to 2C as of 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2023:

So what should our takeaway from all this be?

First, we are almost certainly in for a world that overshoots 1.5C. The remaining carbon budgets is so small that it implies a rate of emissions reductions that will be almost impossible to achieve given both the technological and geopolitical challenges of decarbonization.

Second, while we will very likely pass 1.5C, there are reasonably plausible scenarios that limit warming to around 1.8C (with a ~66% chance of avoiding 2C warming by 2100) that do not rely on large-scale net-negative emissions if we can get global emissions to zero by 2070 or so, and even lower if we get to zero earlier than that.

While climate impacts will get more severe in this future, we do not have any evidence that it would risk runaway warming or globally climatically-significant tipping points that 1.5C would not. Every tenth of a degree matters, and the faster we can get emissions to zero the more we can reduce the long-term damages of climate change.

I was going to suggest that, rather than continue to update on the urgent actions necessary to prevent 1.5C, you could better serve public discussion by explaining why preventing 1.5C is a worthwhile goal, especially compared to the costs of achieving the goal.

Even though the Paris Accord back in 2015 declined to officially adopt 1.5C as the commitment, most public discussion since seems to assume that this is the target, that it "must" be met, and that we face inevitable catastrophe if we don't. Yet, I'm not aware of any scientific data supporting this idea, or even any plausible scientific claim.

Then, I got to the end of your column, "Every tenth of a degree matters, and the faster we can get emissions to zero the more we can reduce the long-term damages of climate change." I guess this is all one can say. But it doesn't justify any particular level of effort to achieve any particular reduction in emissions.

Zeke, I'd love to hear your take on whether AI can help us figure out solutions that the mass of humanity will accept and actually enact. Do you think that's something we should pursue?