Is this the most embarrassing error in the DOE Climate Working Group Report?

mistaking detection for emergence

In the last few weeks, I’ve often been asked, “What’s the most significant mistake in the DOE Climate Working Group Report?” While the report contains numerous issues, one in particular stands out for its far-reaching implications. I write about it in this post.

A recent report from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Climate Working Group (DOE CWG) attempts to analyze and critique the findings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In doing so, the DOE CWG Report makes several fundamental errors due to a misunderstanding of the peer-reviewed literature.

One in particular stands out, as it leads the authors to incorrectly represent the established science on extreme weather.

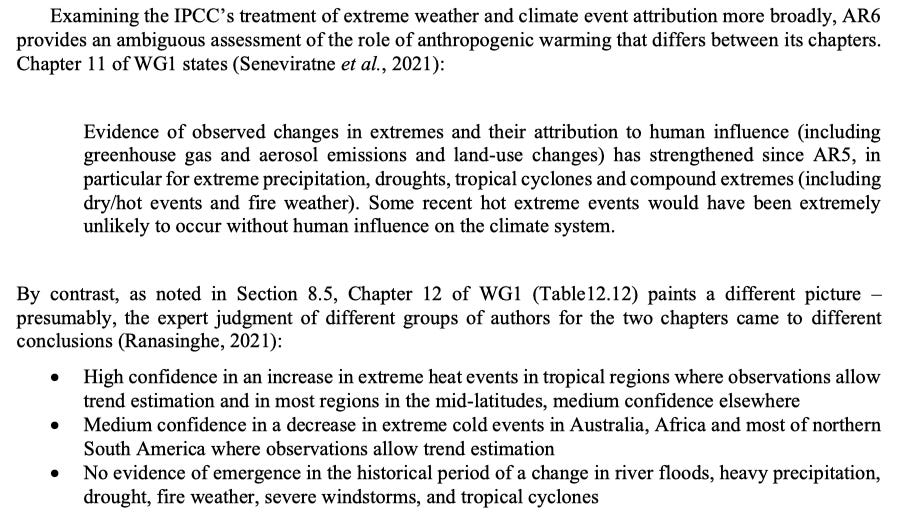

Section 8.5 of the DOE CWG Report focuses on a single table in the IPCC report (Table 12.12 in the Sixth Assessment’s Working Group 1 Report) and, based on this table, concludes: “it is not currently possible to attribute changes in most extreme weather types to human influences.”

With this statement, the CWG demonstrates that they have no idea what they’re talking about.

confusing “detection and attribution” with “emergence”

Table 12.12 isn’t about detecting whether humans are making extreme weather more extreme. That work — known as detection and attribution — is detailed extensively in other parts of the IPCC report, particularly Chapter 11.

For example, at the end of Section 11.4.4, when talking about extreme precipitation, they state:

In summary, most of the observed intensification of heavy precipitation over land regions is likely due to anthropogenic influence, for which greenhouse gas emissions are the main contributor.

You can also see attribution statements connecting humans to, for example, extreme heat and some types of drought.

Chapter 12 and Table 12.12 are about something different and much stricter: emergence.

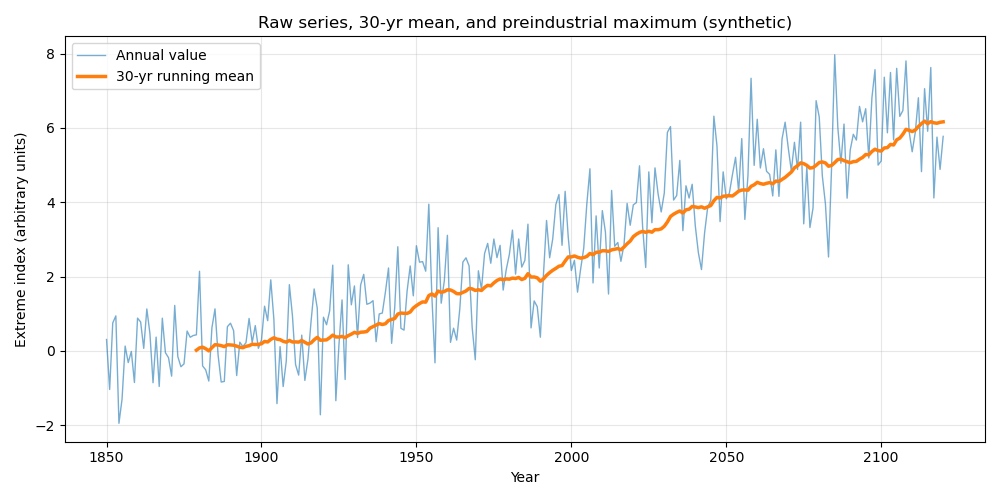

To understand the difference, let me give you an example. Imagine you have a data set that is an index of some kind of extreme weather:

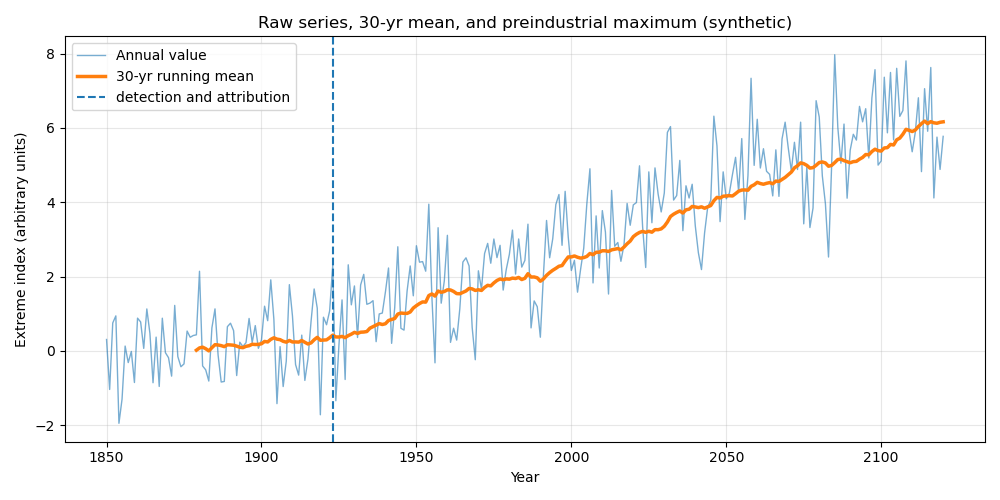

Detection and attribution identifies a statistically significant change in the parameter of interest. In this case, I determine the date of detection as the first year when there is a statistically significant difference between the 30-year running mean and the pre-industrial mean:

Note that detection and attribution says nothing about the size of the change. It only says that the climate has shifted. If you have really good data and a long time series, you can detect small changes in a parameter

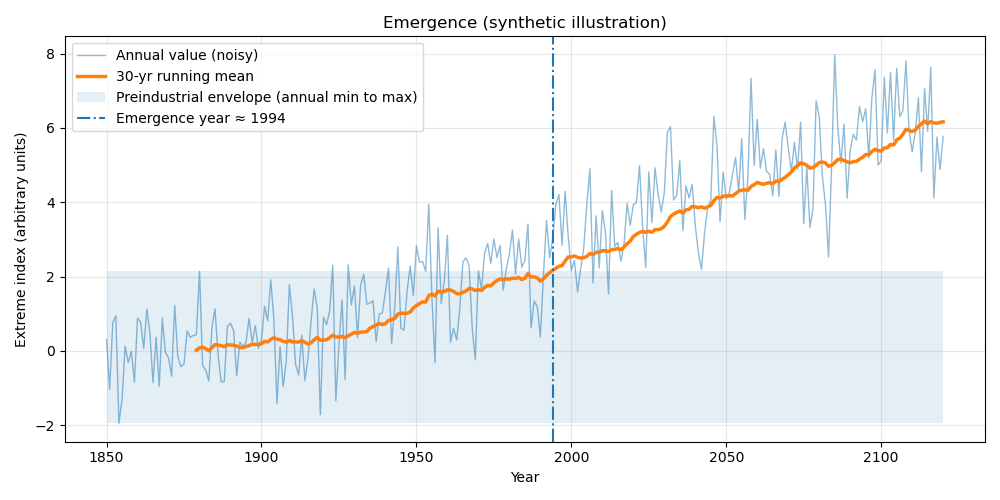

Emergence is all about the size of the influence. It means that the climate has shifted so much that the average value of some parameter is larger than the largest value in a pre-industrial climate. In other words, you’ve emerged into a new climate.

Here is emergence in the example data set:

The plot shows that the 30-year running mean (orange line) exceeds the pre-industrial range (the shaded region) in the mid-1990s. That’s the time of emergence. [Update: I should have used standard deviation of pre-industrial values, not the full range. My bad.]

Because emergence requires a large shift, it’s a far rarer occurrence than simply detecting and attributing a trend in some weather parameter.

I should note that my simple example above really focuses on detection. Detection and attribution research uses sophisticated techniques to identify a trend and assign its cause to human influence through, e.g., the use of fingerprints (e.g., a cooling stratosphere).

For example, recent work by Santer et al. (2025) showed that, had humanity had the quality measurements we have today, they could have detected and attributed global average warming to humans by the late 1800s.

the central flaw in the DOE Report’s argument

Many parameters have trends that have been detected and attributed to human activities (Chapter 11) but have not yet changed so much that they have emerged (Chapter 12).

The entire argument in Section 8.5 rests on this single, critical misunderstanding of these distinct concepts. This leads the authors to arrive at a demonstrably incorrect conclusion: “it is not currently possible to attribute changes in most extreme weather types to human influences.”

In fact, the extensive attribution findings detailed in Chapter 11 of the IPCC report make it clear that humans are indeed influencing extreme weather.

The authors of the DOE CWG report appear to have noticed this discrepancy. On page 95, they write:

Given this puzzling (to them) disconnect between Chapters 11 and 12, they could have spent some time digging into this to understand it. They could, for example, have actually read the IPCC reports and supporting literature. Or they could have emailed a few experts and asked why chapters 11 and 12 reached seemingly different conclusions.

But they didn’t. Instead, the authors expended zero effort to get the science right.

And, believe it or not, there are even more errors in this section. If you want to see the full list of mistakes, see the full comment on Section 8.5 beginning on p. 316 of the Climate Experts’ Review of the DOE CWG Report.

how to think about the DOE CWG Report

The errors in the DOE CWG Report are significant. The effect of these errors is to generate conclusions that cast unwarranted doubt on established climate science. As I’ve said before, the generation of unwarranted doubt is the same strategy that the tobacco industry used to delay regulation in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s.

It’s also worth noting that the errors in Section 8.5 also prove that the report never had any legitimate peer review. It only took me 30 seconds of reading this section to realize, “Oh, they f*cked this up.” Anyone familiar with climate science would quickly identify this error, so the fact that this was not caught means any “peer review” the report had before it was released was a fiction.

If the DOE is committed to a legitimate debate over climate science, the scientifically appropriate step would be to acknowledge and correct this and other identified errors. So far, that has not happened.

In fact, they’ve taken the opposite tact. For example, Steve Koonin wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed in which he declared: “Though scientists supporting the so-called consensus on climate change have organized several serious critiques [of the DOE CWG Report], these at most add detail and nuance to our findings, without negating the report’s central points.”

To suggest the identification of this core error in Section 8.5 merely “adds detail and nuance,” as Steve Koonin did, is laughable. Our analysis of Section 8.5, along with our analysis of other sections, directly falsifies the report’s core assertions about climate change’s impact on extreme weather.

This serves as a litmus test for the report’s scientific credibility. A commitment to scientific integrity requires the authors to produce a point-by-point response to the expert comments, overseen by an independent review editor.

A refusal to do so would suggest that the report should be viewed as an advocacy piece rather than a scientific document, and its conclusions should be treated with caution.

While this post focuses on one section, the rest of the DOE CWG Report is not much better. The entire document contains a pattern of errors, including simple errors of understanding, misinterpretation of source material, cherry-picking of data and sources, and selective citation.

The public and policymakers deserve a more accurate and rigorous scientific assessment of climate science for decision-making. I suggest that the U.S. Government withdraw this report and instead establish a transparent assessment of climate science that follows best practices for credible assessments. They can call it the National Climate Assessment.

other things you should pay attention to

This is a really good video about the impact of increasing CO2 on plants

“As Solar Dominates, the Sun Sets on the LNG Boom” on Powering the Planet

I’d be grateful if you could hit the like button ❤️ below! It helps more people discover these ideas and lets me know what’s connecting with readers.

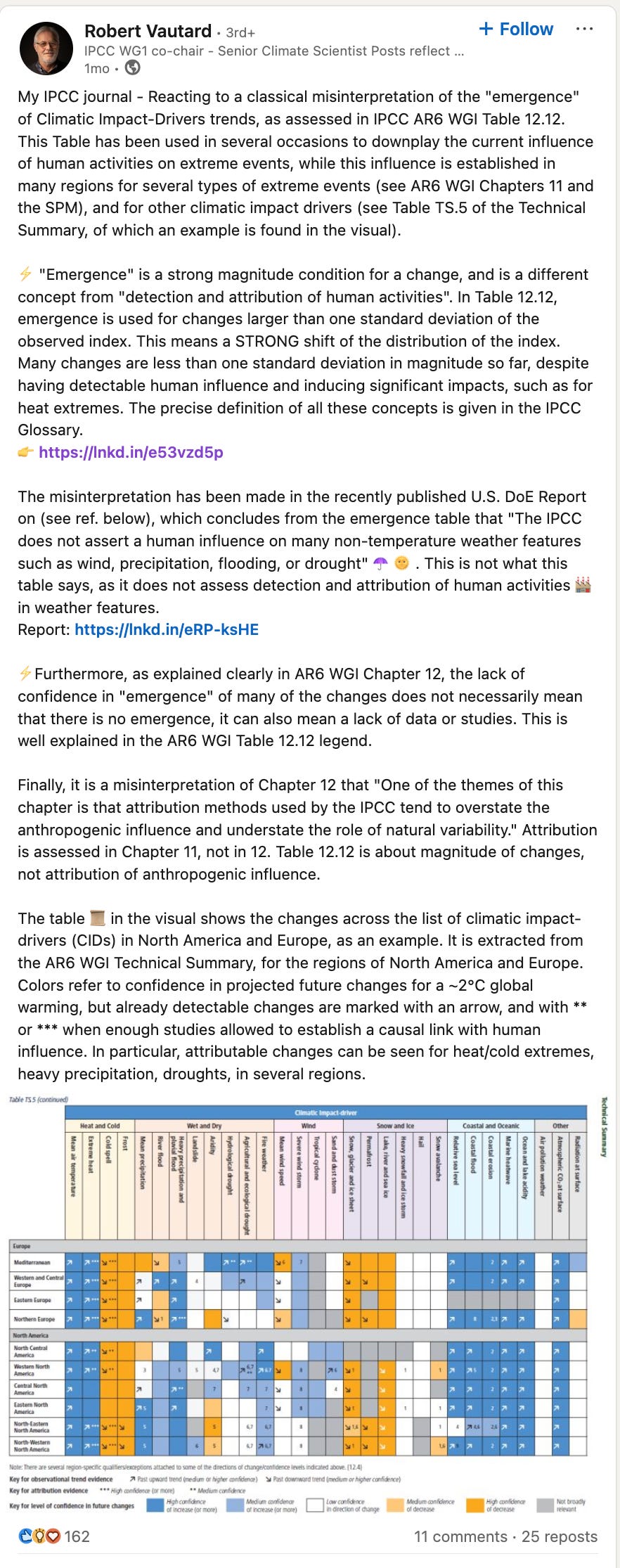

Update: a prominent climate misinformer is claiming that I am not interpreting the difference between emergence and d&a correctly. Prior to writing this, I talked to one of the coordinating lead authors of Chap. 12 and he confirmed my interpretation. Another coordinating lead author of Chap. 12 wrote the post below on LinkedIn, which also confirms my interpretation.

Andrew, I think by now given this administration's attitude towards climate science that any such errors are not by accident or lack of understanding. Any report that says climate change is in any way anthropogenic would not be published. The NPS has been ordered to remove any signs that discuss changes due to climate change (among other things Trump doesn't like https://grist.org/politics/why-trumps-purge-of-negative-national-park-signs-includes-climate-change/ ) so I wouldn't count on this being an "error" that could be corrected.

I wrote a response to this piece.

Andy has introduced a definition of ToE at odds with IPCC and things go downhill from there

https://rogerpielkejr.substack.com/p/bunk-from-the-brink

Andy if you'd like to write a response, I am happy to publish it

Comments welcomed