How rising water vapour in the atmosphere is amplifying warming and making extreme weather worse

Kevin Trenberth explains

My friend and colleague Dr. Kevin Trenberth has written an article for The Conversation about water vapor, one of my favorite topics in climate science. Kevin is one of the most distinguished atmospheric scientists in the world and his thoughts are always worth listening to. He mentioned to me that “Unfortunately the length got cut and all details are missing”, so I asked whether he wanted to publish the more complete version of his article. He said yes, so here it is. I added a few links but resisted the very strong temptation to change “vapour” to “vapor”. AED

By Kevin Trenberth

The northern summer of 2023 has seen a string of record-breaking disasters related to climate change. These range from major wildfires in Canada, Maui, Greece and elsewhere, to catastrophic flooding from Beijing to Vermont, extensive prolonged heatwaves with temperatures over 100°F in the U.S., and rapidly developing hurricanes such as Hilary, Idalia and Saola (typhoon). Earlier in the year there was major flooding and damage in New Zealand associated with a rain bomb (January 27, 2023), and cyclone Gabrielle in February 2023. Sea temperatures have been at record high levels and July 2023 is the hottest month on record. Antarctic sea ice is at record lows for southern winter. To many, this seems like an acceleration of the human-induced climate change. And it is. But it is not unexpected by scientists.

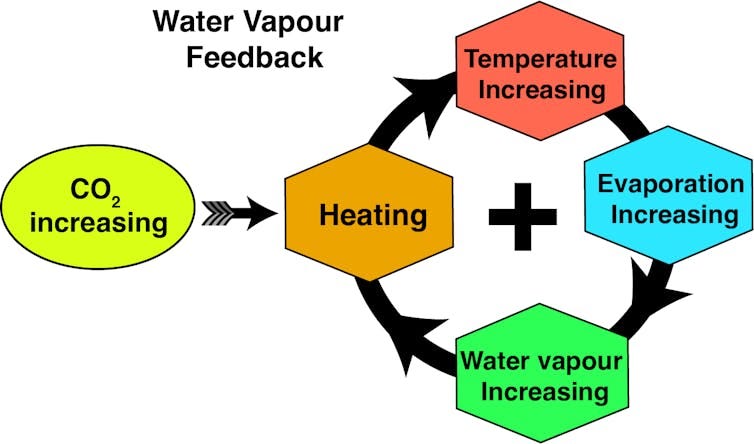

Climate change is brought on by human activities, most notably burning of fossil fuels putting increasing amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. However, this is not what has caused the acceleration in disasters. Rather it is the well-known positive feedbacks within the climate system that play off the changes otherwise forced on the climate system and amplify the changes. They depend on the temperature changes and heating already going on. Most notable is water vapour feedback.

As the Earth and its oceans warm up, the water-holding capacity of the atmosphere increases at a rate of about 7% per degree Celsius (or about 4% per degree Fahrenheit). And the record high sea temperatures ensure that there is more moisture in the form of water vapour in the atmosphere as a result. Estimates are 5 to 15% relative to prior to the 1970s, when global temperature increases began in earnest.

But water vapour is a powerful greenhouse gas. The increases have likely increased global heating by an amount comparable to that from increases in carbon dioxide. And we are seeing the consequences!

Water Vapour: the other greenhouse gas

Many people are unaware that water vapour is a powerful greenhouse gas. In many ways, it is the most important greenhouse gas as it makes living on Earth viable. But human-induced climate change is primarily caused by increases in long-lived greenhouse gases (GHGs): carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons).

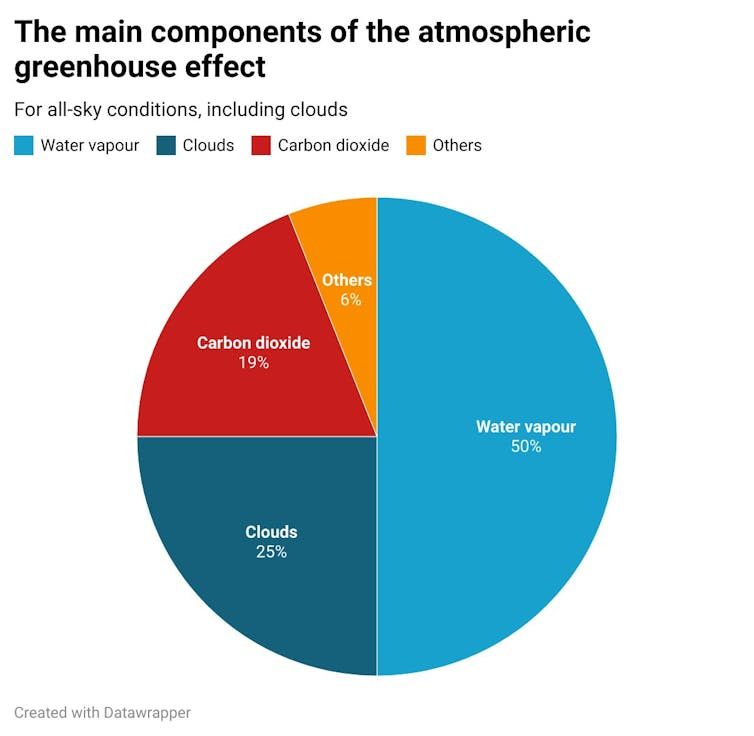

As a general rule, molecules with three or more atoms are greenhouse gases, owing to the way the atoms can vibrate and rotate within the molecule. A greenhouse gas in the atmosphere absorbs and re-emits thermal (infrared) radiation and has a blanketing effect, as the emitted radiation is usually at a lower temperature than the Earth’s surface. Accordingly, water vapour (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) are greenhouse gases. Clouds have a blanketing effect similar to that of greenhouse gases but clouds are also bright reflectors of solar radiation and thus also act to cool the surface by day. In the current climate, for average all-sky conditions, water vapour is estimated to account for 50% of the greenhouse effect, carbon dioxide 19%, ozone 4%, and other gases 3%; while clouds make up a quarter of the greenhouse effect.

The main greenhouse gases of carbon dioxide, ozone, methane, and nitrous oxide do not condense and precipitate as water vapour does. The result is orders of magnitude differences in the lifetime of these gases (decades to centuries) compared with about nine days for water vapour. Hence, they serve as a stable backbone of the atmospheric heating, and the resulting temperature is what enables the observed levels of water vapour. In this regard, carbon dioxide is the single most important greenhouse gas. [ed note: See also Richard Alley’s great 2009 AGU talk about this, The biggest control knob, which explains how carbon dioxide maintains the level of water vapor in our atmosphere].

Carbon dioxide increases do not depend on weather, but arise primarily from human activities burning fossil fuels. Atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased from pre-industrial levels of 280 ppmv to 420 ppmv now, an increase of 50%. About half of that increase has occurred since 1985. It produces global heating and accounts for about 75% of the anthropogenic heating. The rest is mainly from methane and nitrous oxide, while offset by pollution aerosols. However, as temperatures increase with warming, the amount of water vapour also increases and results in further warming as a positive feedback. Since the mid-1970s this extra heating from water vapour is on a par with that from increased carbon dioxide.

Water vapour varies tremendously in space and time

Water vapour is the gaseous form of water, and it exists naturally in the atmosphere. It is invisible to the naked eye, unlike clouds, which are composed of tiny water droplets or ice crystals that are large enough to scatter light and become visible. The most common measure of water vapour in the atmosphere is relative humidity, which is the percentage water vapour present compared with the maximum amount at saturation.

You have probably heard the saying “It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity”. For heat waves and warm conditions, this indeed applies to human comfort. The reason is because evaporation of moisture from your skin, sweat or perspiration, produces evaporative cooling. But if the environment is too humid, then it wanes and your body instead becomes sticky and uncomfortable.

This process is important for our planet, because about 70% of the Earth’s surface is water, predominantly ocean. Hence, extra heat generally goes into evaporating moisture. Additionally, plants release water vapour through a process called transpiration in which water enters the atmosphere through the tiny stomata in leaves as photosynthesis occurs. Together these are called evapotranspiration.

The moisture rises into the atmosphere as water vapour. Storms gather and concentrate the water vapour so that precipitation can occur. As water vapour has an exponential dependence on temperature, it is highest in warm regions, such as the tropics and near the ground; amounts drop off at cold higher latitudes and altitudes. The expansion and cooling of air as it rises is what makes for clouds and rain. And snow. It is because of this vigorous hydrological cycle the average atmospheric life of a water vapour molecule is just 9 days. Although the main water vapour increases may be near the surface, upper tropospheric water vapour is more critically important for the net greenhouse effect. Both are connected every time there is a storm of some sort.

Water is the air conditioner of the planet. It not only keeps the surface cooler, but rain also washes a lot of pollution out of the atmosphere to everyone’s benefit. After a shower of rain, when the sun comes out, puddles tend to dry up before temperatures rise. On hot days, when out hiking, it is important to have a water bottle, or exposure to the sun could cause heat stroke. In the absence of surface water, as in a desert or drought, heat has no alternative but to raise temperatures. Plants wilt, and wildfire risk increases. Water keeps the air cooler, at the expense of making it moister.

Isn’t water wonderful?

Precipitation is vitally important, as it nourishes vegetation and supports various ecosystems, but mainly if the rate is moderate, as deluges can cause erosion and extensive damage. As the climate warms, increasing environmental moisture raises the potential for heavier rainfall or snowfall amounts, increasing the risk of flooding. Moreover, the latent energy that went into evaporation in the first place is given back, adding to the heating and making the air more buoyant, causing it to rise, so that it invigorates the storm which then precipitates even more. Climate change makes the extremes greater and less manageable.

So these changes mean that where it is not raining, drought and wildfire risk increase, but where it is raining, it pours.

Related posts

In Kevin’s doc a couple of times he uses language that tends to confuse people on both sides of the climate change issue. For instance, “ Climate change is brought on by human activities, most notably burning of fossil fuels putting increasing amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.” It should say, “Accelerated climate change……”. Too often, in the general public, the misleading “Climate change” causes unnecessary confusion and polarizes the issue.

His article overall is VERY interesting, but reliable sources should be more careful with the wording to avoid confusion and division in the general public.

This brings to mind the theories of ten or so years ago that no, carbon dioxide has nothing to do with global warming, it’s all due to galactic cosmic rays striking clouds and creating nucleation sites for aerosols ... long since refuted but probably still around as one of many zombie theories deniers cling to. The current paper gives a great summary of the true contributions from various sources.