Canadian wildfires and climate change

What the scientific literature tells us about current and future climate impacts

Yesterday, New York city looked like the outdoor hell-scapes of Blade Runner 2049. Air pollution levels (PM2.5) reached “hazardous” levels, the worst air pollution since modern records began in the region.

Large parts of Canada and the Eastern US were engulfed in haze as nearly 250 fires burned out of control across Canada. These have simultaneously developed in both Western and Eastern Canada.

This has raised questions if this – like the rise of megafires in the Western US – is being fueled by climate change. As we discuss below, there is a clear link between climate change and the hotter conditions and fuel aridity that make “fire weather” and wildfires more likely and more destructive. At the same time, any individual fire may be the result of a number of factors, and we will need to wait until formal attribution studies are done to determine the extent to which the current Canadian fires were made worse by climate change.

Climate change is not the only thing making wildfires worse. A legacy of wildfire suppression has resulted in extensive fuel loading in many forests that prime them for catastrophic wildfires. While mitigating climate change is important to prevent fires from getting worse, even if we get emissions down to zero the world will not cool back down for many centuries to come. Only more effective forest management can reduce the impacts we are experiencing today.

The scientific literature suggests a strong climate/wildfire link

There is broad agreement among researchers that hot and dry conditions increase fuel aridity and fire weather that increase the likelihood of wildfires burning more acres when they occur. This figure from the classic Abatzoglou and Williams paper shows that how the dryness of the fuel is strongly correlated with the area burned. And since warmer temperatures lead to drier fuel, this provides the link between fires and climate.

Similarly, research led by Dr. Megan Kirchmeier-Young found that the 2017 fire season in Canada’s 2017 fire season where around 3 million acres burned in British Columbia was driven “extreme warm and dry conditions” made seven to 11 times larger by climate change.

Future changes in wildfires will vary regionally, depending on the relative changes in precipitation, temperature, fuel load, and ignitions. Some regions, such as parts of the tropics, may actually see less area burned in the future.

As Dr. Crystal Kolden points out that “more extreme wildfires are clearly linked to climate change, and the relationship is strongest at high latitudes, like in Siberia, Canada, Alaska, and Northern Europe.”

Overall, the future is one of more fire. According to a study published by Dr. Xianli Wang and five other researchers at the Canadian Forest Service, “The broad consensus indicates that climate change will cause larger and more frequent fires, resulting in a growing annual area burned in much of Canada.”

The recent IPCC 6th Assessment Report noted that “wildland fire was identified as a top climate-change risk facing Canada” and suggested that projected area burned in Canada using a low-end RCP2.6 scenario would increase annual fire suppression costs to 1 billion CAD the by end of century, a 60% increase relative to 1980–2009 (and up to 119% in a high-end emissions scenario).

How have Canadian fires changed over time?

The Canadian National Fire Database provides is a collection of forest fire data from various sources. Fires of all sizes are included in the database, but a small portion of fires (those greater than 500 acres) account for more than 97% of area burned in most years. The figure below shows both the number of fires and area burned in Canada since 1980.

Since 1980 the number of fires has declined notably, from around 8,000 fires per year in the 1980s to around 6,000 today. The total count of fires is more of an indicator of changes in ignitions (either human-caused or lightning-related), while the area burned is more reflective of fire conditions.

The overall area burned in Canada shows no clear trend, with a number of extremely high individual wildfire years in the 1980s and 1990s, but a small upwards trend since the early 2000s. Its unclear where 2023 will fall with respect to this longer record, but over 3.3 million hectares have already burned and the fire season has only just begun.

How might they change in a warmer world?

While it is hard to detect a clear signal in area burned in Canada to date, there are a number of studies suggesting that warmer conditions over the coming century driven by climate change will increase the prevalence of wildfires.

The figure below, from the IPCC 6th Assessment Report WG1, shows medium confidence of increased fire weather by the end of the century in both Eastern and Western Canada, as well as an upward observed trend in fire weather in the historical record Western Canada (though no clear trend to-date in Eastern Canada). The IPCC defines fire weather as weather conditions conducive to triggering and sustaining wildfires, based on a set of indicators including temperature, soil moisture, humidity, and wind.

A 2017 paper by Dr. Mike Wotton and colleagues found large and significant increases in the percent of fire weather days (where active fire growth potential exists) across different regions of Canada across three different Earth System Models. While this research used the high-end RCP8.5 scenario, a similar (but smaller) effect would occur under more plausible emissions scenarios.

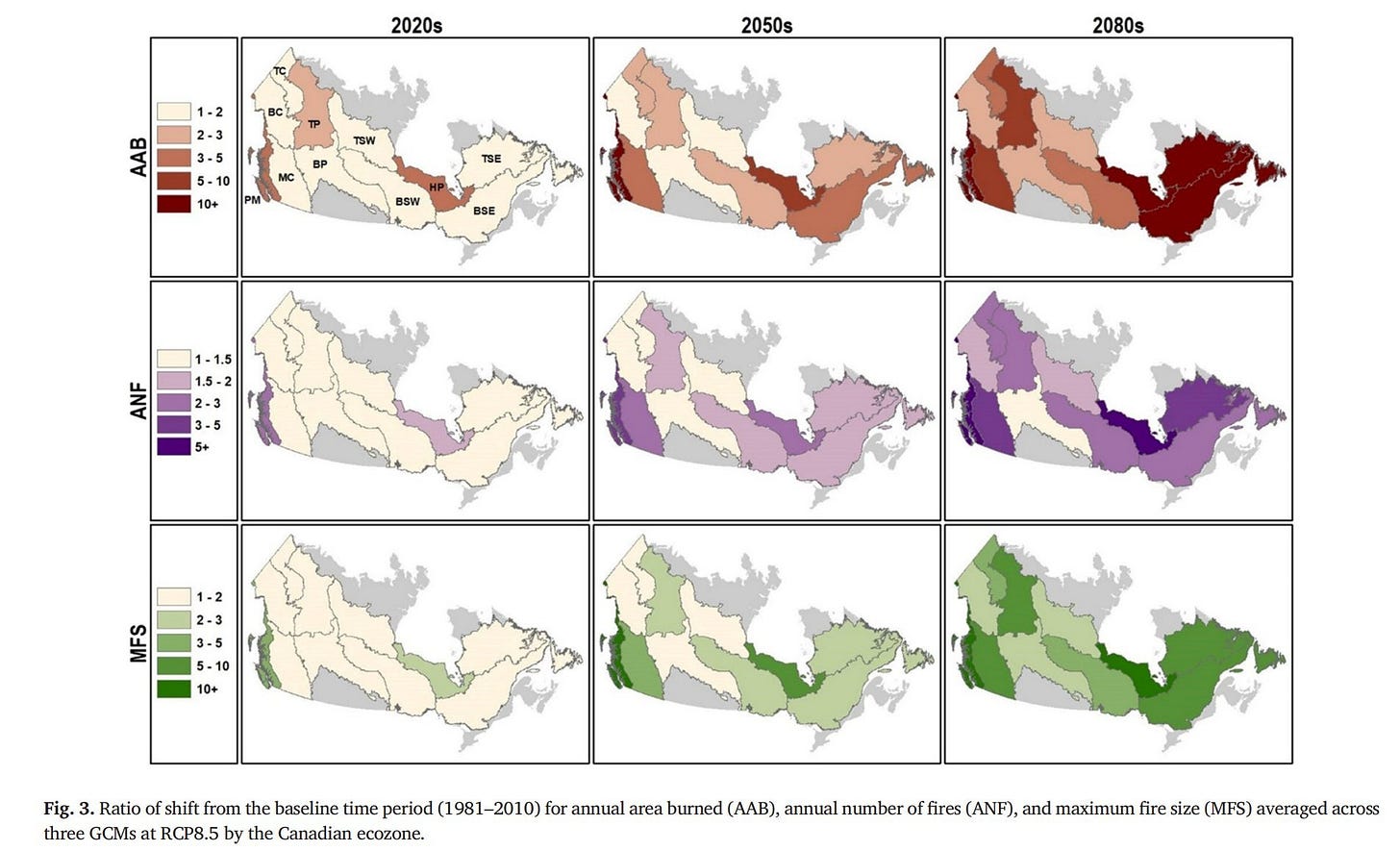

A more recent 2021 paper by Dr. Xianli Wang and colleagues finds similar results, with a large increase in annual area burned, number of fires, and maximum fire size across Canada in a warming world, with a partially strong percent increase in Eastern Canada in the latter half of the 21st century.

Similarly, Wang et al 2020 finds that “across Canada an extreme fire year could be four times more common by the end of the century, and more than ten times more common in the boreal biome (assuming other factors remained constant). That is, an average fire year under the extreme climate scenario may burn ∼4 Mha more area than the most extreme fire year in Canada's modern history (∼7 Mha). By accounting for the strong nonlinear expansion of wildfires as a function of number of fire spread days, even conservative climate-change scenarios yield significant increases in fire activity.”

While more attribution work still needs to be done to determine what – if any – effect climate change to-date has had on the current catastrophic wildfires sweeping through Canada, the scientific literature is clear that these sort of events are likely to become more common as the world warms.

Thank you for a good balanced summary.

Thanks Zeke... wonderful summary. -ss